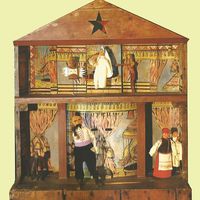

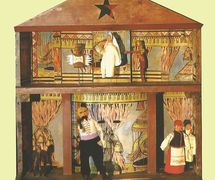

Ukrainian puppet performance representing the Nativity as well as secular material. According to many researchers the vertep (Cyrillic: вертеп, literally “secret place”, “grotto” or “cave” in the old Slavic language) emerged between the end of the 16th century and the start of the 17th century. It was the time of the national liberation movement when Ukrainians began to assert themselves against Polish-Lithuanian domination and the influence of Moscow. At that time, too, the distinctive culture of the Ukrainian nation was appearing. Since peasants and Cossacks made up the majority of the Ukrainian population, it was their tastes and interests that determined the artistic model of the Ukrainian vertep. Both the vertep’s philosophical basis and its architecture (the little, portable box-theatre) make it truly the national form of the Ukrainian puppet theatre.

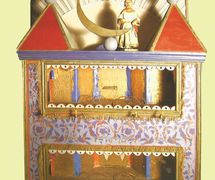

The vertep theatre is dualistic in nature. First there is the story of Christ’s birth as drawn from the Gospels, and then there are stories of the common man, drawn from daily life. The Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorij Savyc Skovoroda believed that vertep actually represented three worlds: that of God, the cosmos, and nature; that of the living; and that of the allegory. The vertep’s drama was staged at three levels: the Celestial, where the deities are sitting; the Biblical, where the Christmas drama is performed; and the Earthly, where the distinctive short scenes, or interludes, of the life of the Ukrainian people took place.

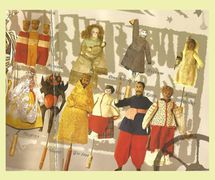

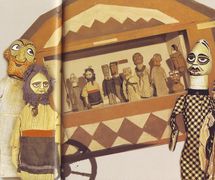

The puppets of the traditional vertep were usually carved of wood and could not move their limbs. Their one, frozen gesture had to convey the essence of their character. These interlude puppets reflected the society of the times: a Zaporozhian Cossack, a Ukrainian peasant, an old man, old woman, a servant, girl, inn keeper, theology student (bursa), a Gypsy, Gentleman, Polish landowner, Muscovite, soldiers, initiate priest, and so on.

The relationships and clashes between these characters illustrated the characteristics, interests and manners of thinking of the various social groups and, more generally, the life and the culture of the Ukrainian people of the time. In these interludes, Zaporozhets, a Cossack, was a central character. He personified courage, patriotism, honour, and recklessness. He is always ready to defend his motherland. This puppet was the largest, with a size of 32 centimetres compared with 24 centimetres for the other figures. He wore a coat (a zhupan) and dark blue or red wide trousers, and had a shaved head and a long black moustache. His typical pose was one arm raised against the enemy in defense of the motherland, while in his opposing hand he brandished a bludgeon, symbolizing power. He embodied the spirit of the Cossack class of the Ukrainian Zaporogues, who were asserting themselves against foreign domination.

In the Christmas drama, characters did not correlate with the actual historical epoch of Christ and they personified social qualities. Thus Rachel was more Ukrainian than Jewish and personified vulnerability; Herod, power and culpability; Mary and Joseph, goodness and gentility; the Magi, hypocrisy; and the shepherds, veneration and the worship of God. The appearance of the characters in the Christmas drama conforms to the ecclesiastical canon of the biblical heroes.

The development of the Ukrainian vertep was influenced by the dramaturgy taught at the Academy of Kyievo-Mikhylev (Kiev Kyiv) and founded on the traditional model of Antiquity: protasis–epitasis–katastasis–peripeteia–catastrophe (exposition-rising action-climax-reversal/recognition-denouement). It was said that the students “walked with a vertep”. The plays combined literary and spoken styles in Ukrainian, Old Slavic, Russian, Polish and Hungarian, with these languages being divided into three styles (“high”, “middle”, and “low”) according to the genre and end purpose.

The vertep box-like stage was highly portable, thereby allowing this to be an itinerant and widely seen art form. The vertep was also accompanied by music and dancing. In the common life interludes, the Cracovienne, the Kamarinskaya, and the European dance were seen.

Through the use of image-based thinking (metaphor, allegory, aphoristic character) and the reflection made possible by using the puppetry art form to reveal the artistic essence, the vertep was able to vividly represent the world and aspects of man himself. Because of this, the Ukrainian vertep became the bearer of the spiritual, aesthetic and moral values of the times – the keeper of the historical experience of the Ukrainian people.

Repressed by the Communist government of Soviet Ukraine since the Russian Revolution of October 1917, this form of theatre had all but ceased to exist. Now, however, thanks to the efforts of dedicated reformers of the Ukranian stage, its artistic heritage is being preserved and revived in contemporary Ukrainian theatre.

(See also Nativity Scenes, Ukraine.)

Bibliography

- Fedas, I. E. Ukrainskiy narodniy vertep (v issledovaniyakh 19-20 vekov) [The Ukrainian Folk Vertep (Research of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries)]. Kiev, 1987. (In Russian)

- Franko, I. “Do istorii Ukrainskogo vertepu 18 veku” [History of the Eighteenth Century Ukrainian Vertep]. Zapiski Naukovogo Tovaristva [Proceedings of the Scientific Association]. Vols. 71-72, 1906. (In Ukrainian)