Traditional rod puppet theatre from West Bengal in north-east India. In Bengal, the tradition of puppetry has been traced back to the end of the 14th century. Danger (dangér) putul nach theatre (dance of the wooden dolls) accentuates sung drama in the style of jatra, a kind of popular opera. The puppets’ dancing and acting do not, however, neglect the episodes of the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas. The southern region of western Bengal has the largest number of itinerant troupes travelling from village to village during the wintertime, which is the dry season. During this period, the puppeteers – small farmers or landless day workers – find themselves far from home and seek out fairs and village associations. In certain families, mostly Hindu but sometimes Muslim, the men are fourth generation puppeteers. Religious dogmatism does not influence the expression of the shows. The puppeteers have great respect for their puppets, which are often considered to be sacred. Even though the level of education of the puppeteers is basic, they show great imagination and vitality in their performances.

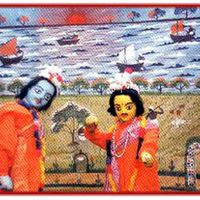

Western Bengal danger putul nach puppets are composed of a wooden body and face covered by a cloth soaked in dry clay that is then painted. The design of the features as well as the primary colours that are used recall the patas (drawings, scroll paintings) by street storytellers. The shining puppet’s face is varnished at least once a year. The wooden hands, pierced with a hole in the palm, can hold a bow, an arrow, a spear or a sword. In the body of each puppet, several removable heads can be alternately inserted, allowing for a change of many characters. The left arm of the puppet is usually not articulated but the right arm has an elbow and sometimes a wrist. The dancing puppets are articulated at the hip and at both wrists. The character of Krishna (avatar of god Vishnu) has a right leg whereas all other puppets do not.

Each ensemble is composed of twenty to twenty-five puppet bodies that can be multiplied by a factor of at least three, thanks to the interchangeable heads, to make up the total number of characters. Some of these heads can also represent animals, such as a lion or a monkey.

The puppet, when its costume is fully spread out, can measure up to 1 metre high and weigh between 5 and 15 kilograms, so that not even a strong man can hold and fully handle a figure of this weight. An ingenious system called kere allows for the manipulation of these heavy puppets: the back of the puppet is extended by a thick bamboo rod inserted into a sheath on the front of the puppeteer’s belt. Holding the rod with the puppet’s head in one hand, and another rod attached to a system of strings to handle the puppet’s two arms in his other hand, the puppeteer looks like he has an additional chest. A visual fusion is created between the puppet and the puppeteer, as the puppet’s height is only slightly lower than the human’s size. So closely attached to the body, the puppets, manipulated one by one, follow the songs and dialogues that they bring to life just like in opera. Attached to the puppeteer’s legs are bell anklets called gunghroo; and as the sound follows him when he walks offstage and into the crowd, a total blending of man and object occurs.

The stage, made of bamboo posts and fabric, can be as high as 3 metres, forcing the spectators to tilt their heads way back to look at the puppets. The stage, measuring 6.5 by 3.5 metres, is closed off on three sides and covered by a cloth roof. The painted backdrops represent a palace, a forest or a cremation ground, and can be changed two or three times during a show.

At the beginning of a performance, the puppeteers and musicians perform an opening ritual chant. The puppeteers then climb on to the stage while the musicians sit on the ground, stage right, near the bamboo posts and start to play a type of oboe, the flute, the kansi (a rod smoothed out on a copper plate), and the nagara (a double kettledrum covered by skin). Sometimes a violin and a harmonium are added to accompany the Bengali language modern-day pop songs. Among the musicians are a lead singer (who often also composes melodies) and three men (nowadays, sometimes women can also be singers) who function as a soloist-chorus group. There are eight musicians and the entire troupe can be comprised of fifteen to eighteen people.

The first scene represents Krishna talking with his adopted father. The entire performance lasts three or more hours depending on the mood of the lead singer. When the troupe appears at fairs, it stops the performance after forty-five minutes or an hour.

For modern productions, the puppeteers do not make new puppets but dress the old ones with new, adapted clothing. Nowadays, some actor-puppeteers use microphones. On demand, modern shows can be set up in two days and the puppeteers invite theatre and especially movie actors.

The Bengali danger putul nach, which generates great enthusiasm from the local public, appears to be one of the most original and enduring forms of puppetry in all of India.

Today, there are troupes and traditional families performing danger putul nach, some of whom are master puppeteers recognized locally and sometimes nationally for their contribution to the art of puppetry.