The Republic of India (Hindi: Bhārat Gaṇarājya) is a nation in South Asia (seventh largest country by area and the second in population) whose borders have included many kingdoms and ethnic groups over the ages. Different cultural strains include aboriginal groupings, Dravidian peoples of the south, Indo-Persian groups of the north and north-west, north-east groups who may share characteristics with South East Asians, Tibetan influenced groups of the Himalaya foothills, and modern multi-ethnic groups in the globalized cities of New Delhi, Mumbai (Bombay), Chennai (Madras), or Kolkata (Calcutta). Four religions originated on the sub-continent: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, and during the first millennium CE, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam arrived, contributing to the region’s diverse culture. India (which up to its independence in 1947 included Pakistan and Bangladesh) was part of the empire of Great Britain from the early 18th century. Today, India has twenty-three official languages (as well as more than one hundred major languages and possibly around sixteen hundred dialects); Hindi and English are the nation’s official languages.

Religious, Social, Literary, and Aesthetic Foundations

Puppets, scroll painting narrations, and mask performances are found in many areas. Though there is enormous diversity, there are common traits. In all areas drama, dance, visual design, and music (all needed in puppetry) have been important vehicles of religious propagation as well as entertainment since well before the beginning of the Common Era. One legend holds that the creator god Brahma made the first puppet and its performer to entertain his wife Saraswati. But when the show was found wanting, Brahma banished the artist to earth as a bhat (Rajasthani puppeteer/entertainer).

The earliest reference to puppetry in India is in the Mahabharata, which reached written form around the 4th century BCE though oral stories themselves date to the 9th century BCE. Panini, the Sanskrit grammarian (4th century BCE), and later Patanjali (2nd century BCE), the author of Yogasutra, each mentioned puppets. Tiruvalluvar, the Tamil poet (2nd century BCE) wrote: “the movements of a man who has not a sensitive conscience are like the simulation of life by marionettes moved by strings”. The important 19th century German scholar Richard Pischel (1849-1908) highlighted Indian puppetry and argued that India was the source of Western puppet traditions.

In classical Sanskrit theatre (100-1000 CE), the sutradhara – literally, the “string (sutra) holder” – introduced and directed the play, causing some to argue that the term is borrowed from puppetry. Noted scholar Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) sees an association of the divine and the puppeteer: Vishwakarma, who is the abstract form of the maker god, is seen as the sutradhara who pulls the strings – the destinies of human beings are in his hands.

India has over twenty living traditions of glove puppets, string puppets, rod puppets, and shadow theatre puppetry. In spite of the distinct regional identities of these forms and the many languages and dialects in which they are performed, there are similar features: the story materials of the plays, the centrality of a narrator/singer, the need for musical accompaniment and dance, the structure of the performance, the social and economic context of traditional rural artists, the underlying aesthetic shared with other theatre and visual arts genres, the moral content or worldview, and frequent links with religion, which over time have included cults of local divinities, Buddhism, Jainism, Hindu Shaivism and Vaishnavism, and Islam.

Indian puppetry has a strong connection with the traditional actor theatre forms of the region or state to which each puppet genre belongs. The ritual preliminaries of a performance are shared. Characters like the sutradhara and the vidushaka (clown) of Sanskrit drama appear under different names at the opening of shows. The interweaving of text, song, rhythm and movement, and the evocation of rasa (sentiment) and bhava (emotive state), are elements that make this connection with Sanskrit theatre apparent. Although aesthetic terms used in the Natyasastra (“Book of the Drama”, written between 200 BCE-200 CE) are not routinely part of the traditional puppeteers’ vocabulary, scholars feel the foundation for the regional forms in local languages is linked to Sanskrit drama.

There continue to be strong parallels between the traditional regional dance-drama and puppetry: Karnataka’s yakshagana and yakshagana gombeyata string puppetry, Kerala’s kathakali and pavakathakali glove puppetry, West Bengal’s jatra and danger putul nach rod puppetry, and Assam’s bhaona and putala nach string puppets are interrelated. At the visual level, costumes, headgear, jewellery, make-up, and character types match, so much so that puppet plays often seem to be miniature theatre performances. Rhythm and dance is inherent in both theatres. Puppeteers with ankle-bells may dance backstage while their puppets dance in the front and drummers and other musical instruments beat the bols (drum syllables), which correspond to dance steps. However, further comparative studies of texts, music, and movements are required to understand the distinctness of the forms.

Puppet making is routinely related to the visual art tradition of the region. Consider similarities in the treatment of eyes in 16th century Lepakshi temple murals of Andhra Pradesh and the shadow puppets of the region, the patachitras (iconic paintings on walls, cloth, palm leaves, scrolls) and gopalila kundhei puppets of Orissa, and the patas (paintings, painted scrolls) and danger putul nach rod puppets of West Bengal. References to these picture scrolls can be found from the 2nd century BCE and, for example, a 3rd century text Bhagavati Sutra relates that the great Jain teacher Mankhali Gosala was the son of a picture showman. Buddhist literature mentions charana chitta (mobile paintings) of the punishments of hell, commonly called yama pata (scrolls of the god Yama, ruler of the underworld): even today we find Bengali performers who play hell scenes called yam pot, and contemporary Gujarati panels may show the Lord of Death (Yama) dealing out punishments. These picture narratives are performed with music and movement that reminds us that puppetry and performers and painters often come from the same groups as puppeteers.

Traditional puppet plays in India enact stories of heroes and heroines, gods and goddesses, taken from ancient literary texts such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics and the Puranas (literally “Of Ancient Times”, i.e. stories of various deities), besides local myths and tales. The known stories and simple performances recharge memories of the community and share significant moral and spiritual ideas while also bringing comment on present situations via clowns and other devices.

The stylized iconography of the characters determines the shape, colours and costumes of the puppets. In some genres, puppets speak in their own special language using a reed instrument (see Voice, Swazzle). The art is transmitted from generation to generation, as children assist their elders in performance. Puppetry has been a part of festivals, celebrations of special occasions and rituals, and shows were and sometimes are staged to ward off evil spirits or relieve drought (see Rites and Rituals).

Traditional Puppetry of India

Although a number of traditional forms are disappearing due to modernization, efforts are being made to preserve them and contemporary puppetry, developing in the 20th century, has many noted practitioners in urban areas. The following brief discussion, organized by state, will list prime traditional genres.

Tamil Nadu

Although puppet traditions of the four southern states show similarities due to centuries of migrations, languages continue to create differences. Tamil Nadu in the south-east of India has two major traditions of puppetry, tolu bommalatam shadow puppetry and bommalatam string-cum-rod figures. Both tell the tales from the epics and the Puranas. Pava koothu (glove puppetry), which almost died out, represents the victory dance of Goddess Lakshmi after she destroys demons.

Tolu bommalatam (“leather puppet dance”), now extremely rare, was reportedly created by migrants from Maharashtra and is related to the shadow puppetry of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, though the Tamil Nadu figures are slightly smaller. One performer and an assistant give the show. Sometime performers now use cardboard figures. Folk tales as well as the epics and Puranas are presented.

Selvaraja Shadow Puppet Group (director A. Selvaraja) in Tirukalukundram, 60 kilometres from Chennai, is a family group that has adapted to present child welfare, community health, population control, and other “social awareness” themes, and does children’s shows. Another group, Indian Puppeteers (director S. Seethalaxmi), founded by Chennai shadow master M.V. Ramanamurthi, has performed in Europe, the United States, and throughout Asia, staging the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Lord Ayyappa, and Panchatantra (animal fables).

L. Rajappa (b.1952), an eighth-generation puppeteer from a family of tolu bommalatam performers, received the nation’s prestigious Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for his contribution to the art form in 2007. The Sangeet Natak Akademi is India’s National Academy of Music, Dance and Drama.

Bommalatam (“doll/puppet dance”), which is also common to bordering areas of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, was patronized by the kings of Tanjavur in the 18th and 19th centuries and presented in villages and temples to propitiate gods, bring rain, or prevent disease. The performance opens with a ritual puja (worship) to Ganesh, the elephant-headed son of God Shiva. The 10-kilogram figures are about 90 centimetres high and have rods attached to the hands. A cane or iron ring with the strings attached to the figure is worn on the puppeteer’s head. Rods attached to the puppets’ hands are manipulated from above. Characters roughly move in the style of bharatanatyam, the classical dance of the region, and can even play with a ball (ammanattam). Music is drum (mridangam), oboe (ottu), gong (jalar), and cymbals. One male and one female singer are needed. Old Thanjavur puppets are elegantly carved, finely dressed and decorated; contemporary figures are simpler. A character like the god Indra will have an elephant head tied to his waist to signify Airavata, his animal mount.

The Sri Rama Vilasa Kattabommu Nataka Sabha in Chinna, Siragapatti in Salem district, and Mangala Gana Bommalattam Sabha and Sri Murugan Sangeetha Bommalatta Sabha in Kumbakonam are some current troupes. The latter group was spearheaded by the nationally recognized T.N. Sankaranathan, whose son, T.S. Murugan, now leads the troupe; he has introduced a keyboard and modern stage lighting to attract new audiences.

Kerala

This south-western state has three puppet genres, tolpava koothu (tolpava kuthu; shadow puppetry), pavakathakali (glove puppetry), and nool pavakoothu (string puppetry). Performances tell the two epics and stories from the Puranas.

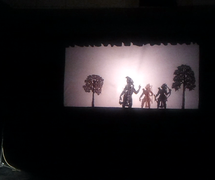

Tolpava koothu is traditionally performed by the Vellala Chetty, Nair and Ganka communities with the puppeteers called pulavar (scholar, poet). Lead performers infuse complex ideas into performances. Puppeteers’ palm leaf manuscripts of the Ramayana by the Tamil poet Kambar (Kamban, 9-13th century?) – Ramavataram, popularly known as Kamba Ramayana – are the basis for the show, which lasts between 7 and 21 nights and is dedicated to Bhadrakali (Goddess Durga). It is said she was busy fighting the demon Darikasura during the actual events experienced by Rama, so she likes to see the story via shadow performance during her temple festival. A permanent puppet stage (koothu madam) faces the goddess’ image and 21 coconut oil lamps illuminate the screen. The temple oracle ritually lights these lamps from the deity’s votive lamp. Rituals open the show, which uses approximately 130 deerskin puppets (48-80 centimetres). Five or more puppeteers perform to the powerful percussive music.

K.K. Ramachandra Pulavar (b.1960), director of Krishnan Kutty Pulavar Memorial Tolpava Koothu & Puppet Centre at Koonathara, comes from a puppeteer lineage and performs in India and internationally. His late father, K.L. Krishanan Kutty (1926-2000), received the prestigious Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1980 for his lifetime dedication to his genre of puppetry art. Since 1979, Ramachandra has also innovated new plays on contemporary issues.

Pavakathakali (“glove puppet kathakali”) is found today in Irinjalakuda. This genre, developed in the 18th century, uses the complex stories of the classical Kerala kathakali dance drama. The spectacular headdresses, face painting, and complex music of the actors are reiterated. Carved wooden figures are 30-60 centimetres high – the head is moved by the index figure and arms by thumb and middle finger. The puppeteer is visible and the performer’s active eyes interpret emotions, as the performer melds with dancing figures. Language mixes Malayalam and Telugu. Performers, from the Adhi Pandaram community, came from Andhra Pradesh and were specialists in leading pujas and pilgrimages to the shrine of Subramanian (a son of Shiva).

This almost extinct art was revived in 1982 by Natana Kairali Research & Performing Centre for Traditional Arts based in Thrissur, under Gopal Venu (b.1945). Sangeet Natak Akademi, then under the leadership of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, had granted the initial financial assistance for the training programme in the art of pavakathakali, including training in music, manipulation, and puppet-making. The revitalized pavakathakli has performed nationally and at international festivals, including in Poland (1984), Japan (1986), and Switzerland (1987). In 2010, troupe artists K.V. Ramakrishnan and K.C. Ramakrishnan were jointly honoured with the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, and Ravi Gopalan Nair received the Dakshina Chitra Virutha Award.

Nool pavakoothu (“string doll dance”) was confined to Ernakulam District and presented by Nair caste members patronized by royalty at temple festivals in Tripunithura (Thrippunithura) telling stories from the epics or folk narratives. By the mid 20th century it was extinct, but then revived. Figures are 60-80 centimetres high. A female dancer tossing a ball opens the show and is followed by the amusing dialogue between two clowns, Koru and Unnaikan.

The mask performance kummatti is a processional performance where people wear masks of Krishna, the god Narada, the Elephant Ganesh, hunters, and old people (i.e. the “mother of the universe”) appear carrying agricultural products and, clothed in skirts of plaited grass, exorcise evil as they visit homes to music of a bowed stringed instrument (onavillu) played with a bamboo stick. Tiger dance (pulikali) is another mask/body puppet genre. Spectacular costumes of theyyam oracles, who divine in trance, while not strictly puppetry, are visually linked to both kathakali and puppet imagery, as is, too, the masked ritual dance-drama, mutiyettu (performed in the Kali temples, specifically in Kali’s manifestation as Bhadrakali), and also the animal masks used in krishnattam which presents the Ramayana in a dance drama.

Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh, where Telugu is the main language, boasts four traditional puppet forms: tolu bommalata (shadow puppetry), koyya bommalata, keelu bommalata, and sutram bommalata (all three string puppetry). All these traditional puppetry forms of Andhra Pradesh perform episodes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

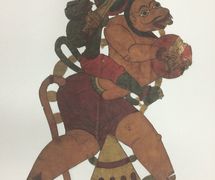

Tolu Bommalata (“leather doll play”) was brought to Kerala by migrants from Maharashtra in the 17th century. Settling on Andhra Pradesh’s border with Karnataka, they developed the form developed in both states. Puppeteers spoke a dialect of Marathi at home, but local languages for their performances. Plays are improvised based on King Kona Reddi’s Telugu version of the Ranganath Ramayana (13th century) while Mahabharata stories are derived from yakshagana dance drama texts. The translucent coloured puppets are up to 1.8 metres high and usually of goatskin. Figures appear in profile with the exception of the ten-headed demon-king, Ravana. Traditionally, figures’ clothing reflected yakshagana costuming, but more recently tight coats, shoes, and socks are depicted. Figures moved freely at head, neck, shoulders, elbows, and wrists. Dancing puppets (keelu bommalu) have their feet separately stitched. A central bamboo stick attaches to the figure’s head and two sticks are attached to the hands. The 3 metre by 2.4 metre white cloth screen tilts at the top toward the audience, and about eight performers of both sexes present. Singing, speaking, and dancing the characters, they stamp on wooden planks and use their ankle bells to create sound. Drum (mridangam), harmonium, and cymbals (talam) add music. Performances would be held for Shivaratri (birth of Shiva) Festival for nine nights, with performances lasting up to eight hours an evening. Ritual openings honour the elephant god, Ganesh, and goddess of learning, Saraswati. Then comes the sabha vandanam (greeting of the audience) and the sutradhara introduces the theme, and comedy is provided by the character Kethigadu and his wife Bangarakka (also, Killekyatha and Bangaraku).

K. Chinna Anjannamma (b.1957) was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for his work in this genre in 2010. Chhaya Nataka Brundam is group led by S. Chidambara Rao who comes from a traditional puppetry lineage. Sri Nataraja Nilaya Charmachita Kala Pradarsana Committee is another group that has added new works incorporating such social topics as HIV/AIDS awareness, family planning, and deforestation into epic stories. Anjaneyulu Shadow Puppet Theatre, lead by Hanumant Rao, does performances of Sundara Kanda telling of the exploits of Hanuman, based on Tulsidas’ 16th century version of the Ramayana. Puppeteers struggle to adapt to contemporary audience needs.

Koyya bommalata (“wooden doll play”) is documented by the 12th century and was widely found until the 20th century. Costume and music were analogous to the local yakshagana theatre, with the same colourful headdresses and acrobatic dance routines. Stories told were from the two epics, local myths, or folk tales. Figures are 1.2 to 1.65 metres high and the skirts of the figures create an illusion of even greater height. The play is shown on a 3-metre stage formed by a cloth stretched between two poles. Thirty to a hundred figures may be used for a performance.

M. Upplaiah from Ammapur village of Warangal district performs the Ramayana, mythical plays, and some wonder tales like Balanagamma Katha (in which Princess Balanagamma is kidnapped and changed into a dog while imprisoned).

Karnataka

The earliest references to leather puppetry in Karnataka are from the 10th-11th centuries and string puppetry is associated with Basavana (Basava), a saint poet of the 12th century. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the kings of Vijayanagara patronized marionettes. Shadow and string puppetry were prominent, while simple chinni patti – glove puppets played on one hand and kartal (cymbals) with the other – were also performed by mendicants.

Togalu gombeyata (“leather puppet dance”) performs the two epics (especially the 15th century Kannada Torave Thorave Ramayana by Kumaravalmiki), stories from the Puranas, and folk tales. Figures echo costuming and iconography of local theatre and painting traditions. Puppets are of two variants. Chikka (small, .30 to 1.2 metre) figures are found in Mysore, Bellary, Bijapur and Raichur; they are manipulated while seated. Dodda (big, 1.8 metre) figures are found on the border of Andhra Pradesh and are manipulated while standing. Performers are from the Killikyeta (Killikyata or Killekyata) tribe of Maharashtra and speak a dialect of Marathi; however they use Kannada for local performances. Performances are on a stage set up outside the village or in a temple courtyard. As in Andhra Pradesh, Ganesh, Saraswati, and the comics (here Killikyeta and his wife Bangarakka) appear at the opening. The singer, drum (mandalam), cymbals (tala), and ankle-bells (gejje) are prominent.

Sri Annapurneshwari Leather Puppet Mela, a 5-member shadow group led by Virupaxappa Kshatrix from a traditional family, has toured internationally. Belagallu Veeranna (b.1936) from a Killikyeta family has trained his children and also developed a new work on Gandhi’s life, Bapu, presented at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) in New Delhi. In 2011, he received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award.

Ramaiah, the son of famous puppeteer T. Hombaiah (1900-?, recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1995), and K.S. Sanjeevamurthy are other notable traditional shadow masters. Patronage is limited.

String puppetry has three major styles: southern style which is related to Tamil Nadu and uses larger figures and hands that are moved by rods; the northern style which is a string puppet tradition and gives special importance to the comic character; and a third, the coastal style, which is very close to its yakshagana theatre.

Names may vary. Sutrada gombeyata (“string puppet dance”) is found in the south and is similar to Tamil traditions. Gombeyata is the usual name in the north. Yakshagana gombeyata (“string puppet yakshagana”) is the name in the coastal district and it may take elements from north and south. Performances reflect local variations on yakshagana dance drama in costume, movement, and music. Themes are drawn from the epics and Puranas and moulded by Shaivism and Vaishnavism. The carved wooden puppets are up to 1 metre tall and weigh up to 8 kilograms. The puppets in the south do not have legs: skirts mask the lower body. In the north, legs can be visible and complex dance manipulation shows off dance footwork. Six strings attach the figure’s ears, hands, and knees going up to three wooden control sticks. Puppeteers speak for their figure and a narrator-singer (bhagvathar) plays cymbals (tala), with other musicians on the maddale and chende drums, harmonium, and oboe (mukhaveene). A booth with a playing area of 1.8 x 1.2 x .75 metres is usually erected outside a temple. Salaki gombeyata (or rod gombeyata), like Tamil traditions, uses string and rod manipulation: an iron ring placed on the head of the performer with strings attached reaching down to the puppet and rods attached to the figure’s hands for operation. The puppeteer pushes the figure with his knees for forceful movements.

The yakshagana gombeyata troupe, Sri Ganesha Yakshagana Gombeyata Mandali, is led by director Bhaskar Kogga Kamath, son of Kogga Kamath (1921-2003) who was a 1979 Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee who claims a 350-year lineage and did yakshagana coastal style puppetry. K.V. Ramesh, a graduate from the University of Calicut, learned with the late Parthi Subba and performs string puppets in Kannada, Malayalam, and Tulu languages. Sri Gopalkrishna Yakshagana Bombeyata Sangha in Kasaragod has shifted from string figures to rod puppets. M.R. Ranganatha Rao (b.1932) is a multi-faceted director, designer, singer, composer, author, and educator from Bangalore who was trained in traditional yakshagana bommalata by his grandfather. Rao’s Garuda Bommai body puppets are 2.1 metres tall and are used during ratha yatra (cart festivals) in South Indian temples. He does new and traditional work with his group Ragaputhali, which has toured in India and abroad. Ranganatha Rao received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1981. A 15-member troupe, Puthali Kalaranga, is specialized in traditional bommalata puppetry and is performed by youth at Bangalore using modern techniques but traditional themes under director Dattatreya Aralikatte who directed Purana Kathamala, a TV serial in Kannada, Tamil, and Telugu. B.H. Puttaswamachar (1924-?) was the recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1999 for sutrada gombeyata.

Maharashtra

The area of Paithan has been an important cultural centre for painting and the related tradition of chitrakathi or picture narration in which the performer explicates the sequence of images. Puppetry in this region is called chitren dekhavane (picture showing) and painters/puppet makers/narrators/puppeteers are from the same families. In Gudiwadi, Pinguli, and Ratnagiri districts near the Goa border, two puppetry forms are found.

Chamdyacha bahulya (chamadyacha bahulya; leather puppetry) is performed by the Thakar community. It is believed that kithli bhavali khel (“bark cloth/paper puppet play”) was precursor to the leather shadow figures.

Kalasutri bahulya (string puppetry) present Ramayana materials. The singer with musicians on drum (tabla), stringed drone instrument (tuntune), cymbals, and conch sit in front of the playing stage. An invocation to Ganesh begins the show. The small figures wear skirts that create the illusion of the lower body. Three strings run from the figure’s two hands and head to the control held in the hand of the operator. Performers present the same stories in picture narration form.

Ganpat Sakharam Masge (b.1958), from Pinguli village in Sindhudurg District, is currently the principal exponent of kalasutri bahulya. He performs with his group of musicians, manipulates all the puppets, is the main narrator, and is the group’s director. He was honoured by the Government of India with a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 2005.

Rajasthan

Kathputli ka khel (“wooden-puppet play”) is the string puppetry of Rajasthan in the north-west of India. Performance style links to traditions of puppetry and popular entertainment in the north-west and on to Iran. Performers are called nats or bhats and present plays during the dry season, returning to farming after the rains. Puppeteers claim divine origin for the art and say they descend from performers patronized by Maharaja Vikramaditya (1st century BCE) of Ujjain: bhats saw the thirty-two (batai pachisi) images carved on his throne representing his great works and were inspired to make figures to tell of his exploits – the Simhasana Dwatrimshika (Thirty-two Tales of the Throne). Forms related to Rajasthan are also found in areas of neighbour state Gujarat.

Kathputli are up to 60 centimetres. The bodies of the figures are stuffed with rags, and skirts give the impression of legs for most figures: they are colourfully costumed in medieval-style Rajasthani dress. Figures earlier were created by craftsmen in the Sawai-Madhopur, Basi, and Udaipur areas, but are now made by puppeteers themselves. Puppets share visual iconography with local phad or painted scrolls (1.5 x 5 metres) of picture narrators (bhopa) that depict the divinized hero Pabuji (a 14th century Rajput king) or Dev Nayan (a new incarnation of Vishnu).

Two string beds are used for the booth covered with colourfully embroidered cloth arches to give the look of a palace. Most figures have one long string, which attaches to both the head and the back, and loops over the manipulator’s fingers. The dancing girl (Anarkali) has up to four strings so she can have additional movements. The puppeteer wears a bracelet of bells (ghungroos) and uses a piece of split bamboo (boli) to create the puppet’s voice. The drum (dholak) player speaks with and interprets the language of the puppet. Comic dialogue and songs of the female singer/interpreter enliven the performance. Shows pivot around the sequential performances of acrobats, dancers, snake charmers, the drummer Khabar Khan, horse riders, and a bahurupia (impersonator who has two heads – male and female – one hidden under his skirt until the puppet flips). The eponymous title of the work is Amar Singh Rathore, after a ruler of Nagaur in the 17th century. He is called to the court of Badash (variously believed to be the Mughal Emperor Akbar or Emperor Shah Jahan). Two communities, Hindu and Muslim, can be distinguished by beards and costumes. Hirni Aur Shikari (shikari means “hunter”) and Ruthi Rajkumari (Princess Ruthi, a Rajput woman warrior) are sometimes listed as other stories.

Performers of the bhat community traditionally lived at the bottom of the social scale and few have successfully transitioned into modern performers. A notable exception is Puran Bhatt (b.1952?), from a traditional family, who founded the group, Aakar (Shape), in 1991 in Kathputli Colony, Shadipur Depot, Delhi. The group, which tours nationally and internationally, performs for schools and television. Aakar creates shows on social issues and experiments with rod, string, shadow, black light theatre, and mask forms. Puran Bhatt’s contemporary piece Carvaan tells the legendary history of kathputli performers. He was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 2003. Another Sangeet Natak Akademi Award winner from Rajasthan is Naurang Bhat (1937-2007), who received his award for kathputli puppet making in 2006.

Uttar Pradesh

Gulabo-Sitabo is a simple glove puppet tradition believed to date from the 17th century and performed out of doors in the Lucknow region. It is rarely performed today. The eponymous characters are two wives of the same husband. Gulabo is domineering and Sitabo is dominated. Humorous dialogues, songs, and fights prevail. Puppets are 60 centimetres and heads and hands were carved and painted wood, but now papier-mâché. The figures wear bells on their wrists. Costumes are traditional female attire and jewellery. One manipulator improvises the dialogue, accompanied by musicians on the drum (dholak) and cymbals (manjira).

Orissa (Odisha)

Vaishna themes in the Oriya language form the major traditional repertory of this east India state. Krishna’s youth and the exploits of Rama – as related in the Srimadbhagwat (Eternal Tales of Supreme Lord), Gita Govinda (Love Song of the Dark Lord, by Jayadeva, 12th century), Puranas and Oriya Ramayana – are themes for puppet dance and song. Orissa has shadow, string, glove, and rod puppet forms.

Ravanachhaya (“Ravana’s shadow”) is the Oriya shadow form; popular in the late 19th century in the Anugul (Angul) and Dhenkanal districts, it is found today only in the Odasa area of Anugul. The Ramayana by poet Vishvanath Khuntia (17th century) is the base. Performers are from the bhat community and claim their ancestors received land grants from the rajas of Pallahara. The show takes its name from Ravana, the demon king, because it is believed that Rama, being a god, casts no shadow. Opaque leather from goat/sheepskin is used for most characters, but god figures are made from deerskin and demons from stag skin. Carving is simple for the small (20-60 centimetre), non-articulated, but expressive figures. Important characters have multiple shapes and sizes – thus monkey Hanuman flying away can become smaller and smaller. Trees, mountains, and chariots help create strong screen pictures. The white screen is stretched on bamboo poles with straw mats masking the area below where puppeteers sit on the ground. A ritual accompanies the lighting of the lamp, Ganesh appears, and the village barber and his son provide comic relief. Musicians sit in front of the screen with drum (khanjani), castanets (daskathi), and cymbals (kubuji).

In 1978, Kathinanda Das (1909-1987) was the first master puppeteer to receive national recognition for his contribution to Indian puppetry for ravanachhaya, receiving a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award. Subsequently, in 1998, his student Kolhacharan Sahu (b.1936) who now directs the institute, Ravan Chhaya Natya Sansad, Orissa, was also honoured with a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award. The ravanachhaya group has innovated a new set of puppets, cut to the model of traditional pata scroll painting of the region.

Gopalila kundhei (“cowherder-play puppet”) is a disappearing string puppet form which tells young Krishna’s pranks with the cow herders (gopa/gopi) and his love for Radha. Themes are from the Srimadbhagwat and Oriya poetic songs, especially the Mathura Mangal by Bhakta Charan Das (1729-1813), set to folk tunes. Carved wooden puppets 50 centimetres high are painted – face features and chest and arms with textile motifs, jewellery, and other adornments. Cloth skirt and scarf are added. Three strings run up from the figure’s head and the wrists to the control. The traditional backdrop is peacock feathers. The five itinerant performers in a group include narrator-singers and musicians with drum (dholak) and cymbals; they traditionally travel from village to village.

Sakhi kundhei (“friend doll”) is a glove puppet tradition of the Ahir Kelas of Cuttack, Kendrapada and Dhenkanal districts given by performers who speak a mixture of Bengali and Oriya. The stories of Radha and Krishna are based on texts like Vastraharan, Radha Krishna Milan, and Navkeli, a poem by Banmali Das (17th century). The mandatory puppets are Radha and Krishna, but Kalita and Vishakha (sakhi friends of Radha) are sometimes added. Head and torso are wood and the costume is in jatra (folk-theatre) style. Radha has bells under her skirt that ring as she moves. Itinerant puppeteers sit on a mat with the audience around them. The puppeteer puts the drum (dolak) on his knee and has the puppets play.

Kathi kundhei nacha (“wooden-rod puppet dance”) is a recent reconstruction of an old form. Stories are from the epics or Puranas and begin with an invocation (stuti) and the introduction of the sutradhara. Puppets are 60 centimetres tall, carved, painted, and costumed in jatra style. Strings inside the torso are pulled to move the characters’ arms. Puppeteers sit on the ground behind a screen. Musicians play drums, cymbals, and reed instruments while a multi-person group manipulates.

Maguni Charan Kuanr (b.1937) was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2004) and is currently the best-known exponent of kathi kundhei nacha. He learned this form of traditional puppetry from the Jhara community in his village in Keonjhar district, Orissa, and has improvised within the genre over many years with his company, Utkala Biswakarma Kalakunja. The group addresses modern themes as well as performing the traditional repertoire based on the Ramayana and other mythic sources, but he notes: “Sadly, the art form again awaits passionate puppeteers who could save it in the age of television and cinema.”

West Bengal

The rise of devotional performance in 16th century Bengal with its praise of Vishnu created human and puppet performances popular for hundreds of years. Today, however, puppetry is more likely to draw its repertoire from jatra, an urban popular melodramatic musical theatre, rather than from the epics and Puranas. String, rod, and glove puppetry are traditional forms.

Tarer putul nach (string puppetry), also known as sutor putul, originally drew its shows from the epics and Puranas, bur now from jatra or popular films. Costumes, music, and dialogue emulate the source. Puppets of .60 to .80 centimetres tall are made from Shola pith (a milky white spongy plant of Bengal). Strings are tied to a bamboo control stick held by the puppeteer. Puppets are jointed at the elbows and performers can handle up to two puppets together. Itinerant puppet companies bring up to forty puppets and their booth with painted backdrops. A dance prelude is followed by a song from a character who introduces the play. The narrator speaks for the character and is accompanied by drum (tabla), harmonium, clarinet, violin, and cymbals.

Dhiren Natya Putul Nach Company in West Bengal is directed by Krishna Pada Sardar, whose father founded the group, and Sardar reworks the tradition with his offspring for contemporary audiences The group has fifty plays in the repertory.

Danger putul nach (“rod puppet dance”) uses puppets of up to 1.25 metres tall and from 5 to 10 kilograms in weight, which are carved wood with clay-and-cloth moulded faces. A rod passes through the body and supports the head and arms. The impression of the lower body is created by the figure’s skirt. The central rod is attached to a kere (bamboo cup) attached at the puppeteer’s waist. A shorter rod allows head manipulation. Strings inside the torso attach to the arms at the shoulder and move them. Painting is reminiscent of the painted scroll (pata) tradition of the area. Costumes may include velvet jackets and headgear adorned with gold and silver thread. The repertory includes the epics, jatra, folk stories, and Bengali film narratives. Operatic singing, broad gestures, and declamatory dialogue prevail in the three-hour performances. The booth is made from bamboo poles draped with cloth: puppeteers are masked as they manipulate the figures from below. Painted scenery includes court scenes, forest, etc. A singer and musicians on khol and nagara drums, harmonium, and cymbals assist.

Jadunath Haldar Putul Natch Opera (director, Jagadish Chandra Haldar) is the oldest active rod puppet group in West Bengal and performs stories from the epics and Puranas, Panchatantra animal stories, and works on social issues. This group has performed at Festival of India, USSR, and national festivals in India. Satya Narayan Putul Natya Sanstha, of West Bengal, was founded by the late Kangal Chandra Mondal in the 1980s. Current director Nirapada Mondal has attended new puppetry workshops, studying with modern Bengali puppet theatre director Suresh Dutta, and has produced Raja Harish Chandra (King Harishchandra) and other innovative works including the ecological story Arannyer Rodan (Crying of the Forest): evil characters threaten the environment and animals unite to save their world. Prafulla Karmakar (b.1939) who does performances largely based on the Ramayana and Mahabharata received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for his lifetime contribution to danger putul nach in 2012.

Benir putul (bener putul; glove puppetry) is performed by one or two puppeteers who travel from village to village. It traditionally shows a man and a woman who constantly quarrel. Figures have terracotta heads and wooden arms with bells attached to the figures’ wrists. Benir putul performer Basanto Ghoroi from Midnapore, West Bengal, tells of his family of labourers who would take puppets as they travelled and thereby supplement their income. Basanto and his family now rely on puppetry and perform their folk and educational puppet plays both door to door and at cultural organizations and schools. They also make and sell the puppets. Ramapada Ghoroi is a traditional benir putul exponent who has migrated to Kolkata (Calcutta). His family has performed the form for more than 80 years. His repertoire comes from the epics, with topical touches added to keep pace with changing audiences, including new roles for women or references to Bollywood in lyrics of his songs.

Related forms of Bengal include chhau mask dances or scroll narration –contemporary painters in Bengal create scrolls with traditional and new topics, including the assassination of Indira Gandhi or the events of 9/11 (September 11, 2001).

Tripura

Putul nach string puppets are found in Tripura and are represented by Gopal Chandra Das (b.1943) who was trained by his father in what is now Bangladesh (East Bengal). He moved to Tripura in 1990 and performs throughout the north-east of India. He has been honoured with a Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2011).

Assam

Puppetry in Assam reflects the artistic legacy of the 16th century saint-poet-social reformer Shankardeva who developed the bhaona, the traditional theatre of the area to spread Vaishnavite religion. Puppetry, like other theatre, was used to present devotional materials. Older literature refers to puppetry as tatak and performers as tatakiya or bajikar who animated figures with mechanical devices. The 16th century Bhagavata Purana mentions kashtamaya and daru putula – now defunct wood and shadow puppet traditions. Only string puppetry remains.

Putala nach (“doll dance”), also known as putul nach, putula nach, putula bhaona, or putala bhaoriya, differs by region. In the Kamrup area, bati putula is sometimes traced back to the previously mentioned thirty-two puppets/exploits of King Vikramaditya and royal patronage of bhat in Ujjain. In upper Assam, at the Nutan Kamalabari Sattra religious enclave on Majuli Island, novices performed puppet shows as taught by visiting puppeteers about 1930. The model is traditional bhaona theatre practice for costumes, musicians, and sutradhara. The Ramayana is the most popular theme, though there are some Mahabharata texts. Today, family planning or ecological concerns may be included. Puppets are 45 to 90 centimetres tall and are often made of bamboo slivers covered with clay-infused cloth with joints at neck, shoulder, and sometimes elbow. Figures are usually legless, wearing a skirt. Some demons with expandable necks or animal mounts are included. Three or four strings go to either a bamboo control or just the puppeteer’s fingers. The booth, with a 1-metre proscenium, is covered on three sides by cloth and puppeteers operate the figures from behind. Drum (khol) and cymbal (tal) players stand in front and start the show with an invocation (vadana) and songs. Next, come the comics Kalu and Bhelu who ceremoniously sweep the floor. Chenga or Mastor is another character that comments comically on the present. The head puppeteer uses a swazzle-like instrument.

Mohakhali Putala Natch group from Nalbari, founded in 1885 and now directed by Banikanta Dev Burman, is an old string puppet group in Assam. Rupi Puppet Theatre, from Kamrup, with group leader Abani Sharma, is another traditional putul nach company currently performing.

Manipur

Laithibi jagoi (laithibi jagol; “doll dance”) is the string puppet tradition of Manipur that takes Vaishnava themes, especially Radha Krishna stories for the Rasleela (Play of Krishna), to local music of the drum (mridanga) and khon-pung. The art is said to have been introduced during the reign of Maharaja Chandrakirti Singh (r.1850-1886). Uddhab Singh (1890-1961) was a noted exponent of laithibi jagoi, and Brajomohan Sharma’s family troupe was also important in the early 20th century. Puppets are performed from a 3-metre high stage and often presented as an interlude during dance presentations.

Other Regions of India

In areas of Sikkim, Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and other regions that approach the Himalaya one finds use of masks and sometimes the hobbyhorse or other puppets in performance of Tibetan-influenced groups in ’cham (ch’am or chham) mask performances or lhamo dance dramas. These contribute to the wealth of traditional object theatre in an Indian context. Travelling puppeteers once migrated around the northern part of the subcontinent and probably on to areas that are now Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. Hinduism, with its love of iconographical representations in both divine and demonic manifestations, developed a rich tradition of sculpture. Figures once made were sometimes moved in processions during “cart festivals”, which in some ways relate to puppetry, such as the ratha yatra of Jagannath (“Lord of the Universe”) and two other deities when they are transferred from one temple in Orissa to another in three massive wooden chariots drawn by devotees.

Visual representations can make otherwise un-seeable powers manifest. The inclinations of Buddhists, Jains, Hindus, and today even our modern preachers of HIV/AIDS education, have long turned to puppets. These figures move minds and hearts via the dancing shadows and figures.

Modern Indian Puppetry

A contemporary Indian artistic scene exists since India’s independence. Exchanges with other Asian, European, and American countries have left their mark on urban puppet theatre. New forms and artistic techniques have appeared and contemporary Indian artists no longer only rely on age-old techniques to reinvigorate the field of shadow or puppet theatre, but also introduce new styles discovered abroad. Educated urban artists well trained in modern literature, visual arts, theatre, educational ideas, and social issues have used puppetry as a tool to communicate their visions.

In Calcutta in the 1950s, Raghunath Goswami (1931-1995) created the first events combining diverse types of puppets with his Putulpuri Studio (now The Puppets). In Bombay, Madhulal Master founded the Indian Institute of Puppet with which he mounted large rod puppet performances (for which he used blind manipulators) mixed with marionettes (string puppets). In Udaipur, educator-author Devilal Samar founded the Bharathya Lok Kala Mandal Centre, bringing together a museum, a school, and a puppet theatre. In Ahmedabad, Gujarat, Meher Rustom Contractor (1918-1992), trained in visual arts in London, played an essential role in the Shreyas school and at the Darpana Academy of the Performing Arts in Ahmedabad (1957) where she headed its puppet section. With inspiration in modern visual poetry, she used several different manipulation techniques and many styles of shadow theatre and understood how to reconcile Western and Indian traditions.

Visits to India by puppeteers like Bil Baird, Soviet troupes, the Ţăndărică troupe from Romania, the Australian Tintookies, the Marionnetteatern of Stockholm of Michael Meschke, among others, elevated the interest of young Indian puppeteers and the public, which then led to study trips and research projects, all contributing to the foundations of the modern artistic idiom used today.

In 1960-1961, four Indian puppeteers, Suresh Dutta (b.1934), R.N. Shukla Rahi, Dilip Chatterjee, and B. Sahai, studied for a year at the Central Obraztsov Puppet Theatre of Moscow under the direction of Sergei Obraztsov (see Sergei Obraztsov State Academic Central Puppet Theatre, Gosudarstvenny Akademichesky Tsentralny Teatr Kukol imeni S.V. Obraztsova). On their return to India, Suresh Dutta founded the Calcutta Puppet Theatre, where an entire generation of puppeteers was trained in the epic Russian style of rod puppetry. In this way, Calcutta, where Ragunath Goswami’s group was already working, became a centre for the development of modern professional puppet theatre. This Indian “school” respected the creativity of individual performers, while privileging themes linked to the political, social, economic, and artistic problems of modern India.

After Independence, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (1903-1988) played a pioneering role in the study, conservation, and promotion of popular arts and crafts. Heading the Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA), she focused particularly on puppetry and was, for example, an instigator of the resurrection of pavakathakali (glove puppets of Kerala; see Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards for Puppetry). Other important support came from Kapila Vatsayan (b.1928), a scholar of dance, theatre, and visual arts who held a leading role in cultural politics in India and in UNESCO. She was the founder-director of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) and she helped promote exhibits, research, and education in puppetry and other fields (see Historical Research).

Today, one can find modern puppets in Bengal, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. They appear in the educational sector as well as in performances for the mass audience, focusing above all on showing real life and real situations.

Ranjana Pandey and her group Jan Madhyam (founded in 1980 in New Delhi) concentrate on themes linked to the needs of women and children. Ratnamala Nori of Nori Arts and Puppet Centre (founded in 1987 in Hyderabad) deals with education and social change. Sudip Gupta and Calcutta Puppet Theatre (founded in 1990), influenced by leftist ideologies, bring to light social inequalities and the aspirations of the person on the street.

In Delhi, puppeteers offer performances of larger dimension. Dadi Pudumjee, who trained with Meher Contractor and studied and worked in Sweden with Michael Meschke, went on to create India’s first modern puppet repertory, the Sutradhar Puppet Theatre (1980, later renamed Shri Ram Centre Puppet Repertory) at Shri Ram Centre for Art and Culture in New Delhi, and then, since 1986, has led Ishara Puppet Theatre Trust. Puran Bhatt, mentioned earlier, mixes the traditional and the contemporary in his productions (see Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards for Puppetry). Kapil Dev, a graduate of Salaam Baalak Trust (SBT, founded in 1988), an impressive non-governmental organization working with and for street children, has used puppetry extensively in SBT activities. Anurupa Roy (b.1977), a storyteller-puppeteer-performer who takes on themes of the situation of women, of war and peace, leads Katkatha Puppet Arts Trust (founded in 1997). She received the Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar (Youth Award) in 2006.

In Ahmedabad, Mansingh Zala works with his group Meher (in homage to Meher Contractor), as does Mahipat Kavi, who also worked with Meher Contractor and whose glove and rod puppets are inspired by the folklore of Gujarat.

While in Kolkata, Hiren Bhattacharya (b.1926) of Peoples Puppet Theatre (founded in 1977) works on themes of social justice (see Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards for Puppetry).

These and other contemporary puppeteers are in the process of creating new traditions in a country imbued with tradition. Against all odds they manage to survive, creating a synthesis between the past and the present. They steep themselves in what they find around them: colours, forms, stories, certain that the puppet, like life, is not cut off from the world and that the figure requires the breath of the sutradhar, the narrator, “he who holds the strings”.

Government recognition of the exemplary work of contemporary puppeteers has been strong as exemplified by Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards for Meher Contractor (1983), Suresh Dutta (1987), Dadi Pudumjee (1992), Hiren Bhattacharya (2001), and Mahipat Kavi (2011). Moreover, Suresh Dutta (in 2009) and Dadi Pudumjee (in 2011) received the Padmashree for their contribution to Indian puppetry from the President of the Republic of India on behalf of the Government of India, the fourth highest civilian award in the nation.

Puppeteers founded UNIMA-India in 1986 and have actively contributed to UNIMA International, including Dadi Pudumjee’s work and election as president of UNIMA-international in 2008. Meher Contractor and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay have both been UNIMA Members of Honour.

From their side, foreigners show a profound interest in Indian forms of expression. Their fascination comes at the same time from the strength of both the mythic tales and the artistic form. Not content just to study Indian puppets, they often use them as inspiration for their own creations. Michael Meschke in Sweden and Massimo Schuster in France, taking the tales of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, respectively, have given birth to non-Indian performances that are equally strong and seductive in their syncretic aesthetic. Michael Schuster of Train Theater in Israel developed performances of kathputli and Monkey King (a jataka tale of a previous life of the Buddha).

(See also Arjuna, Draupadi, Sita.)

Bibliography

- Awasthi, Suresh. Performance Tradition in India. New Delhi: National Book Trust, India. 2001.

- Baird, Bil. The Art of the Puppet. New York: Macmillan Co., 1965.

- Bhattacharjy, Ashutosh. Folklore of Bengal. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1978.

- Blackburn, Stuart. Inside the Drama-House: Rama Stories and Shadow Puppets in South India. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5q2nb449/

- Chatterjee, A. ed. Sangeet Natak 98 (Oct.-Dec., 1990). [G. Venu, “The Traditional Puppet Theatre of Kerala”; Jiwan Pani, “Shadow Puppetry and Ravan-Chhaya of Orissa”; K.S. Upadhayay, “The Puppet Theatre Tradition of Karnataka”; M. Nagabhushama Sarma, “The Shadow Puppet Tradition of Andhra Pradesh”; Venkat Swaminathan, “Puppet Theatre & Tamil Nadu”.]

- Chattopadhyay, Kamaladevi. Handicrafts of India. New Delhi: Indian Council for Cultural Relations, 1985, pp. 158-175.

- Contractor, Meher R. Puppets of India. Mumbai: Marg Publications, 1968.

- Contractor, Meher R. “Various Types of Traditional Puppets of India”. Marg. No 3. Bombay, 1968.

- Coomaraswamy, A.K. “Picture Showmen”. Indian Historical Quarterly. Vol. 2. June

- Coomaraswamy, A.K. The History of Indian and Indonesian Art. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1965.

- Dalrymple, William. “The Singer of Epics”. Nine Lives. In Search of the Sacred in Modern India. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc., 2009. ISBN 1-4088-0153-1. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- Dash, Dhiren. Puppetry in Orissa. An Introduction. Bhubaneswar: Institute of Oriental Theatre Arts, Orissa.

- Ethnoscénologie. De la terre à la scène [Ethnoscenology. From the Earth to the Stage]. Internationale de l’Imaginaire. No. 5 (new series). Arles: Babel/Actes-Sud, 1995.

- Gargi, Balwant. Folk Theatre of India. Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1966.

- Ghosh, Sampa, and Utpal K. Banerjee. Indian Puppetry and Puppet Stories. Gurgaon: Shubhi Publications, 2007.

- Ghosh, Sampa, and Utpal K. Banerjee. Indian Puppets. Delhi: Abhinav Publications,

- Ghosh, Sampa. Make Your Own Puppets. Delhi: IMH, 2005.

- Ghosh, Sampa, and Utpal K. Banerjee. Puppets of India and the World. Delhi: NationalBook Trust, 2013.

- “Global Bibliography on Shadow Puppetry (See “INDIA”.)

- http://www.ignca.nic.in/bibsp006.htm.

- Goldbergelle, Jonathan. “The Performance Poetics of Tolubommalata: A South Asian

- Shadow Puppet Tradition”. PhD Diss. Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison, 1984.

- Emigh, John. Masked Performance: The Play of Self and Other in Ritual and Theatre.

- Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

- Gründ, Françoise, and Chérif Khaznadar. Le Théâtre d’ombres [Shadow Theatre].

- Rennes: Maison de la culture de Rennes, 1978.

- Jairazbhoy, Nazir Ali. Kathputli. The World of Rajasthani Puppeteers. Ahmedabad:

- Rainbow Publishers, 2007.

- Krishnaiah. S.A. Karnataka Puppetry. Udupi: Regional Resource Centre for Folk

- Performing Arts. 1988.

- Mair, Victor. Painting and Performance: Chinese Picture Recitation and Its Indian

- Genesis. Honolulu: Univ. of Hawaii Press, 1988.

- Pani, Jiwan. Living Dolls. Story of Indian Puppets. New Delhi: Publication Division,

- Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India, 1986.

- Pani, Jiwan. Ravana Chhaya. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1983.

- “Puppet India.com”. 2001.

- http://www.puppetindia.com/contents1.htm. Accessed 15 April 2013.

- Putul Yatra: An Exhibition of Indian Puppets. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2003.

- Rao, M.S. Nanjunda. Leather Puppetry in Karnataka. Bangalore: Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, 2000.

- Sarma, M. Nagabhushana. Tolu Bommalata. The Shadow Puppet Theatre of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1985.

- Schuster, Michael. “Visible Puppets and Hidden Puppeteers: Indian Gombeyata Puppetry”. Asian Theatre Journal. Vol. 18, No. 1. Spring 2001, pp. 59-68. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/asian_theatre_journal/toc/atj18.1.html. Accessed 15 April 2013.

- Singh, Kavita. “The Painted Epic: Narrative in the Rajasthani Phad”. Indian Painting: Essays in Honour of Karl J. Khandalavala. Ed. B.N. Goswamy. New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi, 1995, pp. 409-435.

- Smith, John D. The Epic of Pabuji. New Delhi: Katha, 2005. ISBN 81-87649-83-6.

- Smith, Karen. “Putul Yatra: Sangeet Natak Akademi’s Swarna Jayanti National Festival of Puppet Theatre”. The Puppetry Yearbook. Vol. 6. Ed. James Fisher. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2005, pp. 17-85.

- “Stringing for Substance”. The Hindu. 6 February 2011.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Tiruchirapalli/stringing-forsubsistence/article1162166.ece. Accessed 11 April 2013. - Tilakasiri, Jayadeva. The Puppet Theatre of Asia. Colombo: Department of Cultural Affairs, 1970.

- UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. [Melvyn Helstien, ed]. Asian Puppets: Wall of the World. Los Angeles: Univ. of California, 1976.

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. “The Ancient and Popular Tradition of Indian Puppetry”. Asian

- Culture. No. 27. Tokyo: Asian Cultural Centre for UNESCO, 1980.

- Vatsyayan, Kapila. Traditional Indian Theatre. Multiple Streams. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1980.

- Venu, G. Puppetry and Lesser Known Dance Traditions of Kerala. Trichur: Natana Kairali, 1990.

- Venu, G. Tolpava Koothu: Puppets of Kerala. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1990.

![<em>A <em>sakhi kundhei</em></em> puppeteer manipulating the glove puppet of Radha, the beloved of Krishna, while playing the <em>dhol</em> and singing the melodies that a<em>c</em><em>c</em>ompany the exploits of Radha and Krishna (<em>Or</em>issa [Odisha], India). Photo courtesy of Sampa Ghosh](https://cdn.urlearning.eu/unsafe/215x180/smart/https://wepa.unima.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/india_26.jpg)