In Mali (officially, the Republic of Mali; French: République du Mali, Bambara: Mali ka Fasojamana), a country in West Africa, the puppet theatre remains one of the most beautiful legacies of tradition. Its origins are so ancient that they cannot be dated, including those of the Bozo fisherman to whom paternity is attributed.

At first, puppets were used in animist rituals. They were venerated objects, used in secret religious ceremonies that involved sacrifice. The goal of these rites was essentially to obtain abundant rain.

In all the Bozo populated regions, puppets were not purely abandoned over time but instead changed roles and contexts, especially under the influence of Islam. Puppets became objects for education and entertainment and their initial forms were enriched by the creation of new characters. A combination of expressively animist and sometimes ritual initiation puppets is often seen on the same stage as the newly created puppets. In general, the initial characters are revealed by a nickname divulging their origin as in the case of the nama or suruku (hyena), emblem of the secret initiation society of the Bamanan (Bambara) kòrè called namani or surukuni, “the little hyena”. In fact, during puppet performances, the namani sometimes plays the same roles of scout and protecting policeman assigned to it by the secret initiation societies. Another example is the kote-komo (Kòtè-kònò), a puppet linked to the komo, the powerful and extremely strict Bamanan (Bambara) secret initiation society. Through this association, the puppet brings meaning to the practice of enforcing discipline and respect of traditional values to young people.

The traditional puppet theatre evolved in this way while growing and specializing according to the ethnic groups and local cultures. Today, with the many possibilities of expression that they offer, puppets have been adapted for the Western theatre. This new modern form differs from the traditional by its stage presentation and its characters, as well as by its method of communication.

The Traditional Puppet Theatre

The traditional puppet is first of all a collective object belonging to a village community. Within the context of an association, the young people organize the elements of the performances and entertainment while heeding the elders who supervise them, ensuring respect for customs and especially discipline.

The young people’s associations, called konoton, do-ton, kote-ton …, among their various names, are organized according to two forms whose roots lie in ancient traditions. In the first, more common amongst the Bamanan and Malinké, those of the same age (flanbolo) go through the rites of passage and various steps of initiation together. Children are admitted between the ages of thirteen and fifteen in the structured associations that use this principle, and they change levels at the end of very precise periods. Each class has a series of puppets under its responsibility, and they discover progressively the secrets of all of the puppets before their retirement set between the ages of forty-seven and forty-nine years old.

The second form in use by the Bozo and the Bamanan along the Niger River is borrowed from the organization of initiation societies that reflect the social organization of Mali’s ethnic groups. Each social class, having a well-defined role in harmony with others, maintains and develops an activity for its survival and, consequently, for the survival of all.

The associations structured according to this principle also form sub-groups (sèrè), more or less independent of one another, which divide the novices admitted right after circumcision. Each sèrè is responsible for a certain number of puppets. The members of one sub-group are not expected to know the secrets of the puppets of other groups before reaching the next age level.

A third form is born with “modernism”, inspired by the previous two. It is differentiated mainly by new styles of organization. This form is mostly seen in the peripheries of town centres.

Whichever structure an association chooses, there is also a group for young women, under the responsibility of an older woman, but they are not involved in activities of creating or manipulating puppets. For them, this remains a do, that is, a mystery, just as much as it is for children, or for outsiders.

These associations play a socio-economic and educational role in the villages. An association generally owns a field that has to be put to good use during the winter months. It also functions as a pool for workers at the service of the population in exchange for a salary. The association serves to organize the festival of puppets, and also to aid the neediest on the occasion of social events: death, marriage, baptism …

The elders provide supervision and decide the date of the puppet festivals on an annual basis. It has been noticed, however, that puppet performances coincide more and more with political meetings and tourist visits.

Puppets and Performances

Being of various forms, puppets represent animals (wild and domestic), human beings, mythic beings, and spirits. They can be divided into three categories according to their design: mask puppets, puppets that are worn, and puppets performed in a booth.

The mask puppets use the physical attributes of the wearer as an integral part of the character. He is hidden by clothing that covers his entire body. Usually he also wears a robe and a fibre skirt over these clothes; the whole is completed by a belt that jingles. Here, the interesting part is the sculpture carved from a single piece of wood worn over the face. This mask indicates the nature of the character and the wearer faithfully executes its precise dance steps. In this category one often finds characters borrowed from initiation societies and characters whose physical attributes play a crucial role in the performance, for example: Yayoroba, plump or ideal woman; Npkotiki, young girl; Konomani, pregnant woman.

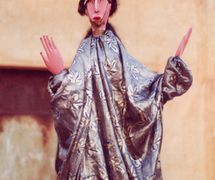

Puppets that are worn are made up of two large parts – the head and the body – that entirely cover the wearer. The head is a wooden sculpture that can include the chest (anthropomorphous characters) and articulations. Its decoration depends on the character it represents. The body is a kind of booth, rectangular or cone shaped, made of vegetable or animal materials, covered with decorative cloth. Sometimes it is a simple form completed by a fancy cloth, or fibres and dried grass reaching the legs of the animator. This is the category with the most delicate and most spectacular puppets such as the lion, the alligator, the serpent, the bird, the Jikando (puppets on the river). Their secret is carefully kept and their manipulation necessitates a long training period.

The booth puppets are small, generally articulated, with care given to realism and the sense of observation. Beautifully sculpted, they are performed in a kalaka (booth) that changes form according to local culture. In Mande and Djitoumou, the kalaka looks like a large rectangular box covered in decorative cloth. It is about 1 metre high and on the surface there are four to six invisible holes through which the puppeteers, who are hidden inside, show the puppets. In Baniko, the booth is rounded with a slight point at the top, and has only three holes. On the banks of the Niger River, from Megetan (Meguetan) to Gourma, the booth resembles more a cart that is in itself a puppet. About 2 or 2.50 metres wide and 2 metres high, this cart personifies a buffalo or an antelope by a large sculpture attached to the front. It is covered with carpets or richly decorated blankets that add value to the sculpture.

The puppets play true scenes of silent theatre. Due to the dexterity of the hidden puppeteers, the movements range from simple dance steps to complicated movements executed by a griot (an historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet and/or musician) who sounds out a clear melody from the drum under his arm.

The role of the traditional puppet theatre is primarily education. Its teachings include married life, social life, economic life, the environment, history and myths, and are transmitted through comic or satirical scenes where realistic or symbolic characters are presented. This theatrical art uses do, the mystery that surrounds the making, manipulating, and language of the puppets, without which it would lose much of its attraction.

Traditional Malian Puppeteers, Mask Makers, and Sculptors

As discussed above, the traditional puppet is primarily a collective object belonging to a village community, performed within the context of an association. Within the association, the young people organize the elements of the performances and entertainment while heeding the elders who supervise them, ensuring respect for customs and especially discipline. The following traditional puppeteers, mask makers or sculptors are among those who have performed a ritual and educational function within their local communities since the early 20th century. They are discussed below by region.

From Diarabougou, Koulikoro Region of western Mali, one of the early 20th century traditional master puppeteers was Baba Traoré (Dinadougou, Koulikoro Region, c.1905 – Diarabougou, Mali, 1940). Born in Dinadougou, he lived in Diarabougou from 1924 until his death in 1940. Baba Traoré founded, in 1927, the famous Do-ton (association of traditional masks and puppets) of Diarabougou. Aided by peers from his own age group, he organized the first annual festival of Do in Diarabougou. They have also created, and when necessary reproduced, the first masks and puppets of the village including Blajan (spirit of the cosmos), Nguman (crowned crane), Bama (cayman), Sah (snake), and Cèkorobani (the old man). Mamady Coulibaly (Diarabougou, Koulikoro Region, Mali, 1951), known as Mamy, is a very hardworking and disciplined traditional master puppeteer from the same area. He has served as an example for the youth of Diarabougou. He impressed the elders of the community through his personal involvement in the organization of festivals of masks and puppets. He drew particular attention for his effectiveness in building unity among the village youth. When the responsibility of the Do-ton (association of masks and puppets) was entrusted to his age group in 1993, he oversaw the diffusion of their work across Mali and internationally. At the end of the term for his age group in 1996, a very rare thing happened. The village council called upon him to continue organizing the Diarabougou Do festival.

Traditional puppeteers from Kouabougou, Sana, Ségou Region include Oumar Koulibly (also spelled Oumar Coulibaly; Kouabougou, Mali, 1918-1993). He was born in Kouabougou, a cultural area of Sana, Sub Prefecture of Sansanding. He is known not only for his performances but also for his role in preserving an annual festival in Kouabougou and perpetuating the art of puppetry in his community. From 1973 to 1975, the town experienced an unprecedented rural exodus due to drought. Many young people had left for urban centres in Mali and neighbouring countries such as Côte d’Ivoire. Therefore, in 1974, for the second consecutive time, the village council decided to defer the annual festival of masks and puppets. As the president of the elders responsible for the association of masks and puppets, Oumar Coulibaly stepped forward and asked for contributions from his age peers. With the money he collected he went to Ségou and Bamako to ask the citizens of the towns to organize and finance the return of those from the village who were key to organizing the festival. He succeeded in his mission and the 1974 festival took place. Hardship conditions did not abate in 1975, but that year the citizens of Kouabougou spontaneously organized themselves to fund the travel of key players. For his part, Oumar Coulibaly used that year’s festival to introduce daytime puppets into the festivities, representing a major innovation.

From Mandé, Koulikoro Region of south-western Mali, Moriba Doumbia (Niègèkoura, Rural Municipality of Sanakoroba, Mali, c.1937), known as Moribani, is a traditional puppeteer currently serving as the village chief of Niègèkoura. His efforts have been instrumental in ensuring that the puppet arts are still practised in the Malinke local community. After the major droughts that affected Mali from 1970 to 1985, the villagers of Niègèkoura decided to abandon the practice of puppetry. Moriba fought for years against the advice of the Muslim community to resume the practice. He still participates in the organization of the festivals and in making the most delicate masks and puppets.

Traditional master puppeteers from Pelengana, Ségou Region in southern-central Mali include Madani Coulibaly (Pelengana, Ségou Region, Mali, 1930-1994), who was born in Pelengana where he spent his entire life. Madani Coulibaly was particularly active from 1945 to the late 1980s. He is credited for helping preserve the art through investments of his own material and finances, as well as his considerable energy. In 1949, Madani Coulibaly created the famous puppet known as Yayoroba (the plump woman, ideal woman), which is still a very popular character. Modibo Coulibaly (Pelengana, Ségou Region, Mali, 1974) is a traditional puppeteer like his father, Madani Coulibaly. Modibo Coulibaly began puppetry at an early age and has been creating puppets for some time. The most famous of his creations is Madani-tle (the time-of-Madani). This puppet, created in 2002 in memory of his late father, currently occupies a prominent place in the collection of the Kanubaanyuma association of Pelengana. The inhabitants of the town of Pelengana currently believe Modibo Coulibaly is essential in organizing and staging their annual puppetry festival. Also from, Pelengana, Bina Koumaré (Pelengana, Ségou Region, Mali, 1943) is a smith and sculptor. Since 1969, he has assumed a critical role in conserving the sculpture of Mali’s ancient puppets. Reproducing these puppets requires the observation of a certain rite. Bina is also a skilled violinist and leads a musical group. Both he and this group have been key to maintaining the traditional combination of masks and puppets of the Kanubaanyuma association of Pelengana.

From Koulikoroba, Koulikoro Region in western Mali, traditional master puppeteers include Mamadou Fofana (Koulikoroba, Somono District, Mali, 1941), who is known for his great passion for puppetry. Among his age group he was distinguished by his outstanding contribution in the manufacture and manipulation of masks and puppets. Even when he became a member of the village elders and served as an adviser to the chief of the district, he remained essential to the manufacture of masks and puppets, including those representing Komadancini (colonial administrator), Madani-sotiki (Madani the cavalier/horse rider), and Bakoronkule (mountain goat). Today, despite his age, he still directs the organization of the mask and puppet festivals of Koulikoroba. Master puppeteer Abdoulaye Diarra (Koulikoroba, Bamanan District, Mali, 1944) is also the priest (French: sacrificateur) of the legendary cult of Nianan and protector of the town of Koulikoro. He contributes to the perpetuation of puppetry traditions in his local community by teaching the young men the dance steps and manipulation of each of the masks and puppets of the Bamanan region of Koulikoroba. Ousmane Fofana (Koulikoroba, Somono District, Mali, 1949) is another traditional master puppeteer of this area. Within his community, he introduced new approaches to the mask and puppet performances and conservation. He is particularly mindful of traditional teachings and regularly transmits these to the young men and to others interested in the art of puppetry in Mali. Due to his concern regarding the gradual loss of the practice, Ousmane Fofana was the first traditional puppeteer to organize a festival which brought together groups from the different parts of the region of Koulikoro.

From Markala, a commune containing thirty villages in Mali’s Ségou Region on the Niger River, Sidy Diarra (Diamarabougou Bamanan, Markala, Mali, c.1946) is a master of the traditional puppetry from the main village of the commune. He is a specialist in puppet making, whatever the category. His assistance is often requested by other communities. His ability to organize festivals after the great drought of the early 1970s is credited with saving the practice of puppetry in his region. He remains very active in such work and is known for the discipline he encourages in the traditional association of masks and puppets of Diamarabougou. Another master puppeteer from Markala, Moussa Diakité (Kirango-bamanan, Markala, Mali, 1954), known as Diago, is distinguished by his intelligence, his passion for the theatre and dedication to puppetry. He has championed young performers and assumed major responsibilities in organizing the annual festival of his local association including puppet making and their staging. Adama Dembelé (Diakaking, Markala, Mali, 1954), another master of traditional Malian puppetry from the Markala region, is involved in all aspects of puppetry in his local community. He is recognized for his ability to organize annual puppet festivals and providing financial support when necessary. He was key to helping puppetry survive the great drought years between 1970 and 1980. Oumar Traoré (Thiorola, Markala, Mali, 1959), another master of the traditional puppetry, emerged gradually in the local association of masks and puppets, performing regularly when other puppeteers were prevented from participating in annual festivals. This allowed him to learn the skills involved in making and manipulating all the puppets in his local community. He now supervises training sessions for the young members of the association.

One traditional puppeteer from Sokonafing (Minkounko), Bamako District, is Sékouba Konaté (1961-2003). He had lived in Minkounko, a locality known by the name of Sokonafing in Bamako. This locality has been rated as a tourist district since 1996 because of its traditional practices, including its puppetry. Upon the sudden death in 1980 of the old Bègnyè Konaté, who had been responsible for the animation of the association’s principal puppet, Kòtè-kònò (the sacred bird of the Kòtè), the inhabitants of Sokonafing were deeply concerned about the future of this important puppet on the eve of the annual festival. The substitute for the master had also died two years previously, and the association had not yet found his replacement. It was then that Sékouba Konaté, at his own request, was commissioned by the elders of Sokonafing to take the place of his master. The 19-year-old was told to simply assume the role of Kòtè-kònò, walking the figure in the playing area during the required period of time the singer and percussionists completed the musical composition. However, the audacious Sékouba did not constrain himself to simply imitate what he used to do with the great Master Bègnyè. Rather, during the annual celebration in 1980, he drew upon his agility, youth and intelligence to infuse the figure of Kòtè-kònò with a new personality. Sékouba Konaté evinced a particularly close attachment to ancestral methods. Unlike many traditional puppeteers of his age, he consulted the spirits and observed all the sacrifices required by oracles before performing with the puppet at the annual festival. With Kola Konaté, a fellow member of his age group who still works for the association of masks and puppets of Sokonafing, Sékouba Konaté never missed an annual celebration from the time he was admitted to the animation of Kòtè-kònò in 1980 to his untimely death in 2003. After the great droughts of the early 1980s, many traditional associations of masks and puppets were forced to close. Sékouba Konaté helped a large number of associations revive their practice of puppetry. As a result, his name appears in several popular songs used to accompany the appearance of the mythical bird of the Kòtè bamanan on stage. For his final act, Sékouba Konaté took care to initiate his first son, Yacouba Konaté, who has replaced him as the animator of Kòtè-kònò in Sokonafing.

The Modern Puppet Theatre

Modern puppets were created in Bamako at the beginning of the 1980s. Partially inspired by the traditional puppets, today they offer performances that more resemble Western theatre whose requirements have minimized the use of ancient local techniques.

Performers might draw from traditional sources as well as techniques to make contemporary theatre. Yaya Coulibaly (b.1959) is the director of the Compagnie Sogolon (Sogolon Puppet Troupe), founded in 1980. The company does Bambara style performance. One contemporary puppeteer who deserves special mention is Aoua Koné (b.1958), the first woman puppeteer of Mali.

This modern theatre started with the adaptation of tales and legends, creating new characters (some in papier-mâché or cloth) that were able to speak (thanks to an articulated lower jaw). The current repertoire offers themes related to major socio-sanitary and environmental problems. In this manner, the modern puppet theatre helps sensitize the population to subjects such as brush fires, tobacco addiction, or HIV/AIDS, and has even been used in a therapeutic manner in the area of mental disabilities.

Because all these subjects are treated with remarkable talent in a form of expression intelligible to all (spoken language), the modern puppet theatre successfully completes the mosaic of traditional puppetry of Mali.

(See also Lassa, Nyogolon Théâtre, Tiory Diarra.)

Bibliography

- Darkowska-Nidzgorski, Olenka. Théâtre populaire de marionnettes en Afrique sub-saharienne [Popular Puppet Theatre in Sub-Saharan Africa]. “Mémoires et monographies” Series II, Vol. 60. Bandundu: Ceeba publications, 1980.

- Darkowska-Nidzgorski, Olenka, and Denis Nidzgorski. Marionnettes et masques au cœur du théâtre africain [Puppets and Masks at the Heart of African Theatre]. Saint Maur: Institut international de la marionnette/Éditions Sépia, 1998.

- Kamian, Bakary. Connaissance de la République du Mali [Knowledge of the Republic of Mali]. Bamako: Secrétariat d’état à l’information et au tourisme, 1965.

- Samaké, Mamadou. “Jeux de masques et de marionnettes à Sokona-fing” [Sokonafing Mask and Puppet Games/Plays]. Revue Culturelle Jamana. No. 7. Bamako, May-June 1986.

- Samaké, Mamadou. “Souvenirs mythiques du pays des anciens” [Mythical Recollections of the Country of the Ancestors]. Marionnettes. No. 21. UNIMA-France, 1989.

- Samaké, Mamadou. Une Exposition sur les Marionnettes du Mali [An Exhibition of the Puppets of Mali]. No. 004. Paris: UNIMA/Éditions l’Entretemps, 2005.

- Sissoko, Sada. Le Kòtèba et l’évolution du Théâtre au Mali [The Kòtèba and the Evolution of Theatre in Mali]. Bamako: Éditions Jamana, 1995.

- Zahan, Dominique. Les sociétés d’initiations bambara: le Ndomo et le Kòrè [The Initiation Societies of Bambara: the Ndomo and the Kòrè]. Paris: Mouton et Co., 1960.