Puppet theatre of the Spanish Baroque period. This was the name (literally, “royal machine”) of the professional theatre companies which, annually licensed in the name of the king or queen or their corresponding viceroyals, via the Council of Castile, were allowed to perform in existing commercial venues – generally the corrales de comedias or “theatrical courtyards” – throughout the Spanish monarch’s territories (Castile, Aragon, Portugal for a few decades, the viceroyalties of New Spain, of Río de Plata, etc.) at least from 1634 to the beginning of the 19th century.

The repertory consisted of the same hagiographic pieces and magic comedies played by the actors, as was the structure of the shows: a prologue, a three-act play, dances and entremeses, almost always ending with a parody of a bullfight – all this accompanied by music. The máquina real companies took advantage of the periods when actors were forbidden to play (above all during Lent) when the puppets performed in the big cities with much success. The troupes consisted of a maestro maquinista (chief machinist or puppet operator), various other machinists and apprentices, between five and ten in total, normally Spaniards. Their shows were frequently shared with other professionals (acrobats and tightrope walkers, for example).

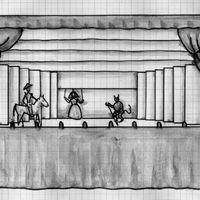

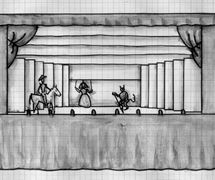

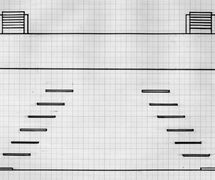

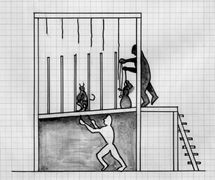

On the stage area of each corral de comedias a wooden structure was erected (about 6.7 by 3.8 metres in size) covered by curtains – this was the máquina – which housed a stage in the Italian style (at least from 1737), with its front cloth, wings and side cloths painted in perspective, and one or more back cloths. Some of the puppeteers, hidden behind the backcloth, performed with puppets with an iron rod to the head, while others seem to have been rod puppets operated from beneath the stage, all of them richly costumed. The settings for the saints’ and magic plays, with their depictions of heaven and hell, apparitions, seascapes and pyrotechnics, necessitated a large variety of stage machinery for the optical illusions and spectacular scenes always so well received by the public; in addition there were measures taken for security’s sake, such as the network of threads forming a mesh screen that covered the stage opening to prevent any flames escaping into the auditorium.

The success enjoyed by these puppet performances was such that a number of the plays – El esclavo del demonio (The Slave of the Devil), San Antonio Abad, Santa María Egipciaca (Saint Mary the Egyptian) – were regularly performed for decades.

The máquina real is the oldest form of commercial puppet theatre to have spread across Europe.

(See Spain.)

Bibliography

- Cornejo, Francisco J. “La máquina real. Teatro de títeres en los corrales de comedias españoles de los siglos XVII y XVIII” [Máquina Real. Puppetry in the Spanish corrales de comedias of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries]. Fantoche. No. 0, 2006, pp. 13-31.

- Cornejo, Francisco J. “Títeres en la ciudad: las representaciones de la ‘máquina real’ en los corrales de comedias españoles de los siglos XVII y XVIII” [Puppets in the City: Representations of the ‘máquina real’ in the Spanish corrales de comedias of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries]. Opinión pública y espacio urbano en la Edad Moderna. Gijón: Ediciones Trea, 2010, pp. 59-76.

- Jurkowski, Henryk. A History of European Puppetry. Vol. 1. New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1996, p. 163.

- Varey, J.E. Historia de los títeres en España [History of Puppetry in Spain]. Madrid: Revista de Occidente, 1957.

- Varey, J.E. Los títeres y otras diversiones populares de Madrid, (1758-1840) [Puppets and Other Popular Entertainments of Madrid (1758-1840)]. London: Tamesis Book, 1972.