Traditional string puppet play from Rajasthan in north-west India. The Bhat and Nat communities of Rajasthan, most originating from Nagaur district, traditionally nomadic but today more or less sedentary, would travel with family throughout the Thar Desert and Nagaur regions practising the profession of putliwallah (puppeteer) and genealogists. As genealogists, they kept the family histories of important people in the villages and towns in Rajasthan where they themselves came from. For their own local rulers, for instance, thrice a day in the square they would recite the family histories, the events in the lives of the rulers’ ancestors.

As puppeteers (kathputliwallah or kathputli kalākāra, “artist”), they perform the kathputli ka khel (“kathputli play”). The kathputli performers claim that their ancestors had performed for royal families and had received great honour and prestige from the rulers of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Punjab. Indeed, they mostly performed in other states, not only in Rajasthan. They travelled to Uttar Pradesh and other areas that were Hindi and Urdu (or Hindustani) speaking, thus the language of the kathputli ka khel – for both songs and dialogues – was a blend of these two languages.

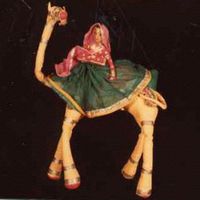

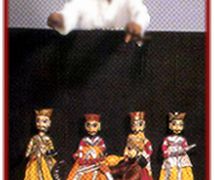

The kathputli puppets (putli meaning doll and kath, wood) are sculpted and painted by the puppeteers themselves, and are composed of a head inserted on a short, thin torso of wood. The arms, made of wood or cloth stuffed with cotton, articulated at the elbow and wrist, hang and move freely on both sides of the body. Since most of the kathputli do not have legs, the puppets’ long, ground-length cotton voile skirts twirl about when in motion. Two strings, one attached around the puppet’s waist, the other to the top of its head, are connected to a loop that the puppeteer manipulates directly between his fingers or lifts to make the puppets dance. The dancer puppet, called Anarkali, however, is a more complex puppet, having around six strings. Traditional kathputli string puppets do not have controls. It is a very simple manipulation technique, yet the result is heightened by the fast movements from above and by the number of puppets assembled on the brightly coloured cloth puppet stage representing a palace.

Today, usually called the taj mahal (in reference to the kathputliwallahs‘ frequent travelling to and performing within Uttar Pradesh, home of the Taj Mahal), the original terms for the kathputli stage referred to its individual parts. Thus, the upper front cloth on the proscenium arches was called jhalar (“fringe”, as in “stage fly”); below were attached the arches (through which the puppets were seen), called tibara; and the black cloth at the rear of the stage (between puppeteer and the puppets) was called kanath (a term still used to refer to the appliquéd cloth wall partitions). All three parts were attached to the “tent”, called tambuda (from tambu or “tent”). In the past, the khandil (hurricane lamps/kerosene lanterns) were placed inside the arches on both sides of the front of the stage to illuminate the scene.

The principal theme of a kathputli performance relates the story of Rajasthani hero Amar Singh Rathore, a Rajput prince of the Nagaur kingdom who lived during the reign of the 17th century Mughal (Mogul) emperor Shah Jahan. In the kathputli ka khel, the Rajput puppet characters are identified by their moustaches and sometimes the cut beard/divided beard, while the Muslim characters wear the pointed beard. Besides the courtiers and noble warriors, both Muslim and Hindu, there are female dancers, musicians, magicians, jugglers, horseback and camelback riders, clowns, and other entertainers that comprise a cast reflecting the splendour of Northern Indian courts.

There are trick puppets – who perform for the court and human audiences – such as the behrupiya, the double-bodied or head-with-two-faces kathputli that changes from male to female, and the jadugar (magician) that juggles his own head. Another notable character and entertainer of the kathputli ka khel is the sapera, the snake charmer. After effectively entrancing the snake with his shehnai (flute), the snake charmer is bitten and killed by the snake, but is then restored to life when the snake sucks out the venom. And there is the charming dancing girl, Anarkali, another popular entertainer.

The principal puppeteer, the head of the family, uses a bamboo voice modifier (boli) to create a puppet language, the whistle-talk (which is unintelligible to the audience) with which he answers the questions of the narrator, who sits outside the stage (see Swazzle). On the other hand, it is one of the women in the family who narrates and sings the text in a language derived from Hindustani (a blend of Hindi and Urdu), a language that the audiences can understand. The principal puppeteer, accompanied by a dholak (a two-skinned drum) and by ghungroo (small bells), evokes the life and exploits of Amar Singh Rathore in the Mughal court, a life that ended with his treacherous death at the hands of a jealous courtier.

Today, the vitality of the kathputli ka khel does not seem to be waning. Many groups of puppeteers crisscross Rajasthan as well as other northern Indian states, particularly since the 1960s “Green Revolution” when an irrigation policy allowed farmers several harvests per year, giving landowning villagers the occasion to give thanks to the gods by celebrating feasts to which they invited troubadours and puppeteers. Often accompanied by Bhopa-Bhopi storytellers from the Bhil group who base their own stories, music, and dances on gigantic comic strip-like painted scrolls (phad or path), the kathputliwallahs‘ most intense period of activity is during the dry season.

Since 1980, several kathputli troupes travel the world over, invited by institutions and festivals.

Today, there are troupes and traditional families performing kathputli ka khel, some of whom are master puppeteers recognized locally and sometimes nationally for their contribution to the art of puppetry.

(See India, Sangeet Natak Akademi Awards for Puppetry.)

Bibliography

- Jairazbhoy, Nazir Ali. Kathputli. The World of Rajasthani Puppeteers. Ahmedabad: Rainbow Publishers, 2007.