The Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: Republika Slovenija), a nation located in southern Central Europe on the Adriatic Coast, borders Italy, Austria, Croatia, and Hungary. Its capital and largest city is Ljubljana. Historically, the current territory of Slovenia was part of many different states, including the Roman Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the 20th century, it was part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929) and then a founding member of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, later renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1991, it split from Yugoslavia and became an independent country.

The Tradition Rediscovered

It was thought that the Slovenes had no indigenous puppet theatre prior to Milan Klemenčič’s work in 1910. However in the 1940s, ethnologist Peter Orel in researching rural dramatic forms found a puppet farce entitled Boundary Dispute, performed at weddings and other celebrations with glove and rod puppets of a specific type.

For this show, the puppeteer was concealed, lying down under a bench which represented the boundary between two properties. On both sides of it he manipulated two puppets. The puppets had a cruciform body covered by a jacket with a hat placed on top; or sometimes a simple stick was pushed through the sleeves of an old jacket and held in its middle by the puppeteer while, with other fingers of the same hand, he held an old hat or cap. This kind of puppet was called lilek or lileki (“moulting”, “skin/hide/body”). Known in Asia Minor, it was introduced by the Ottomans through the Balkans, but the diffusion in Slovenia is not entirely clear: it could have been introduced by soldiers, by seasonal workers, or by refugees, etc. The centres of such puppet plays were the region around Ptuj called Ptujsko polje, the surroundings of the monastery Stična, the region of Suha krajina, the valley Šaleška dolina and the upper valley of the river Savinja.

Such playlets, usually very short, did not have major, permanent or “national” characters; but they still had a bit in common with Petrushka in Russia, Pulcinella in Italy, Guignol in France, Kasperl in Germany, or Punch in Great Britain, in their aggressive and spirited exchanges, insinuations, and the climax in physical beatings between two puppets. The audience was divided into two parties, each supporting one of the protagonists. Conflict resolution was proposed by a live actor playing the role of judge, landlord or some head of the community.

This tradition, well integrated with popular custom, had no impact on the later developments of puppet theatre in Slovenia.

The Beginning of Art Puppetry in Slovenia

The conditions in Slovenia (as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the early 20th century) were not favourable for the development of Slovene drama and theatre. In the years 1910-1914, the Slovene language could already be heard on the stage of the Ljubljana Regional Theatre which was then twenty years old, but it was rare that a play was performed more than two or three times. Recent research, however, has found reference to the staging of Dr. Faust and other puppet pieces before 1900 in Šentjur in the house of the composer Benjamin Ipavec (1829-1909).

It was from the visual arts that the initial impulse to develop puppetry as a theatrical art came. The Slovene painter Milan Klemenčič (1875-1957), influenced by the Italian tradition and by German artists from Munich (see Paul Brann and Josef Leonhard Schmid), founded in 1910 the first Slovene theatre of miniature string puppets at Ajdovščina, in the south-west of the country. Klemenčič then, in 1919, established in Ljubljana a permanent company, Slovensko marionetno gledališče (Slovenian Marionette Theatre), which opened in 1920. Its repertoire included translated plays of Count Franz von Pocci (1807-1976), an adaptation of Sneguljčica (Snow White) by Ivan Lah, and original pieces by Slovene expressionist author Miran Jarc. In Klemenčič’s striving for a Slovene puppet theatre, he was strongly supported by the painter Rihard Jakopič and the architect Jože Plečnik. This new theatre, named after the main character Gašperček (Kasper), was affected by the European puppetry heritage as well as by special, indigenous Slovene features that differentiated it from the European mainstream. However, continuing budgetary difficulties and the lack of a permanent hall forced Klemenčič to close the Slovensko marionetno gledališče in 1924. Though he revived his miniature theatre in 1930, the group had little impact on the ongoing development of Slovene puppet arts.

In the aftermath of World War I, the connections uniting Czech puppetry artists and the Slovenian theatre were apparent, contributing to the formation of over forty puppet theatres within the sports association Sokol (Falcon) which, as in Czechoslovakia, campaigned for Pan-Slavism. With the founding of the Pavliha company, ethnologist Niko Kuret (1906-1995) inaugurated the first Slovenian glove puppet theatre. His hero, Pavliha (wearing Slovenian dress and armed with a hammer instead of a cudgel), replaced Gašperček (Kasper) of Germanic origin.

The Resistance and the Pengov Era

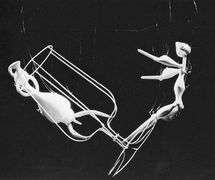

Towards the end of World War II, in the territories that the Slovene Resistance recovered, the Slovene National Theatre performed Shakespeare, Molière and Chekhov, while string puppets designed by painters Lojze Lavrič (1914-1954) and Nikolaj Pirnat (1903-1948) appeared in cabaret performances, ridiculing the occupiers, including Hitler himself. The parody Jurček in trije razbojniki (Giorgie and the Three Brigands), anticipating the end of the war, was popular not only behind the front lines but also in the first few months of freedom.

The foundation of the professional company Lutkovo gledališče Ljubljana (Ljubljana Puppet Theatre) in 1948 ushered in a period of ongoing development. Post-war performances growing from the rich prior experiences and preserved traditions were soon overshadowed by the rise of Jože Pengov (1916-1968), who was determined to raise the artistic status of the Slovenian puppet. An original artist, Pengov completely renewed the Slovene puppetry scene; he eliminated some stock characters and romantic features. He departed from the traditional sculptural design using classic proportions for his puppets, introduced new technical solutions for more dynamic animation, and ended the static approach to directing. He favoured foreign literature, over the poor Slovene writing for the puppet promoting harmony between the figural representation and spoken word. As an adaptor, director and model to others he taught his co-workers to find the best their imagination could offer. He staged around twenty productions, of which half were for string puppets, including Sinja ptica (The Blue Bird, 1964) by Maurice Maeterlinck, Mala čarovnica (The Little Witch, 1967) of Otfried Preussler, and the other half for glove puppets. He chose his designers based on their style, to match the needs of the specific piece. His work focused primarily on the detailed manipulation conceived as a theatrical language in harmonious integration with text and character. His influence extended to the whole federation of the former Yugoslavia.

Professionalization

Until 1968, there was only one professional puppet theatre in Slovenia. This fact stimulated the development of numerous amateur puppet groups. The Lutkovno gledališče Dravlje (Dravlje Puppet Theatre, today Lutkovno gledališče Jože Pengov, Jože Pengov Puppet Theatre), founded by Edi Majaron with his brother Zdenko, was especially active in the mid-1960s and became semi-professional in 1968. Jože Pengov staged his last show, Trdoglavček (Little Wooden Head) by Jan Wilkowski there. This ushered in a period of great diversity for the group in content and formal research – which lasted until 2010, when finances forced closure. After four decades of activity with over sixty performances, the Jože Pengov Puppet Theatre ceased to operate.

In 1973-1974, the Lutkovno gledališče Maribor (Maribor Puppet Theatre, located in the north-east of Slovenia) was founded. Its specialty was musical performances, such as Peter in volk (Peter and the Wolf) of Serge Prokofiev and Leseni princ (The Wooden Prince) of Béla Bartók.

The 1970s to Independence

In the early 1970s, new trends emerged, with entertainments based on strong translations or adaptations of Polish, Czech and Slovak puppet plays. Directors invented new techniques, aided by a generation of artists and designers open to modern trends (notably, Agata Freyer, Breda Varl, and Silvan Omerzu). They introduced a new relationship between the manipulator and the puppet: the puppeteer came out of the shadows to become a visible and a full partner in the dramatic play. This change aroused, in turn, interest in the playwrights – Dane Zajc (1929-2005), Frane Puntar (b.1936), Svetlana Makarovič (b.1939), Dušan Jovanovič (b.1939), Milan Dekleva (b.1945), Boris A. Novak (b.1953) – who wrote for puppets, putting modern clothes on the older mythical foundations and Slovene narratives. Their texts were performed outside Slovenia especially in the former Yugoslavia and in Poland.

The directors of this repertoire – among others, Edi Majaron (b.1940), Helena Zajc (b.1944), Matjaš Loboda (b.1942), Jelena Sitar (b.1959), Tine Varl (b.1940), and Robert Waltl (b.1965) – also contributed to the attention in Europe given to Slovenian puppet productions through meetings and festivals.

Internationalization

Thus, in the 1980s, the Slovenian puppet came out of its isolation. In 1982, a puppet show, Mlada Breda (Young Breda, 1982) by Dane Zajc and directed by Helena Zajc, was incorporated into the programme of the Slovene National Theatre of Ljubljana (Slovensko narodno gledališče (SNG) Drama Ljubljana). Slovenian drama festivals (such as the Festival of the Experimental Minor Stage in Gorica, the Borštnik Drama Festival in Maribor, the Slovene Drama Week in Kranj) included puppet shows in their programmes. They gained international visibility with the Lutke (Puppets) festivals of Ljubljana and the Lutkovni pristan (Puppet Pier) in Maribor.

The Lutkovo gledališče Ljubljana (Ljubljana Puppet Theatre), at the same time, moved to new premises which housed an important collection, foreshadowing a future puppet museum.

Many ensembles were founded after 1990. The most important are: the paper or toy theatre group Lutkovo gledališče Papilu (Papilu Puppet Theatre, today Papelito Brane Solce) of Brane Solce (b.1951) and Maja Solce (b.1954), who work with paper puppets as a kind of “object theatre”; the Paper Puppet Group Papilu of Brane and Maja Solce (today Papelito Brane Solce), Freyer Teater, the Association of Puppet Artists of Silvan Omerzu and Zakonjček; and the very active Mini Teater of Robert Waltl, founded in 1999.

Today, Slovene puppetry explores new paths with directors and actors trained at the theatrical academy of Ljubljana (which however does not have a department specifically devoted to puppets) or abroad. Nevertheless, it is now included as one of the mandatory subjects at the academy for theatre studies (AGRFT) in Ljubljana. Artists from the actors’ theatre seek to meet the aesthetic challenges posed by puppets. Training only exists in a basic form in educational institutes of Ljubljana, Koper and Maribor.

The Profession, Its Endorsements

Slovenia has long been associated with UNIMA. Slovene delegates attended the founding of the organization in 1929 in Prague, and Ljubljana hosted its third congress in 1933. Jože Pengov, UNIMA Executive Committee member, participated in 1956-1957 in the restructuring of the organization. In the 1980s, Edi Majaron, elected to the Executive Committee, organized international meetings of puppetry schools, the Lutke Biennale and, in 1992, the 14th UNIMA World Congress. Slovene puppeteers are active in various UNIMA commissions, especially in the fields of international exchange and the educational mission of puppetry.

The amateur movement, strong before World War II and during the 1960s to the late 1980s, contributed to the aesthetic evolution. The journal, Lutka (1964-2001), reported key global trends and echoed Slovene activities.

The most important collection of puppets is preserved in the Slovenian Theatre Museum in Ljubljana. And although all of the professional theatres have archives, the richest are at the Ljubljana Puppet Theatre, Lutkovo gledališče Ljubljana.