The Commonwealth of Australia, a country in the Oceania region, comprises mainland Australia, the island of Tasmania, and a number of smaller islands. The Indigenous Australians include mainland Aboriginal Australians (who are believed to have arrived some 50,000 years ago), Tasmanian Aborigines, and Torres Strait Islanders (a Melanesian people). Puppetry is not a traditional art form of the Australian Aborigines, although some used carved wooden animals and fish in dances based on myths. Europeans discovered the island continent at the beginning of the 17th century and it became known as New Holland. The eastern part was claimed by Great Britain in 1770 and became a British colony in 1788. Known then as New South Wales it comprised the eastern part of the continent and, until 1841, New Zealand. In 1824, the name Australia was officially adopted but New Holland, which now usually referred only to the western part, was not officially incorporated until 1829. In the 19th century, New South Wales was reduced in size as separate colonies were created and these became states in a federation in 1901, with some independence from Britain. Today (2013), the remaining constitutional connection to the United Kingdom is through the monarch, who is also the monarch of Australia. Waves of immigration from Europe, especially after World War II, and from Asia and Oceania, since the 1970s, have shaped what is today a multicultural nation – and the move from what was dominantly a British culture has been reflected in Australia’s puppetry.

Early British Influences

The British began to settle Australia in 1788 and early puppetry, from about the 1830s, was dominated by English forms, sometimes coming via America: marionettes (string puppets), Punch and Judy and mechanical theatres.

In 1875-1876, McDonough and Earnshaw’s Royal Marionettes (see Bullock’s Royal Marionettes and Thomas Holden) from the United States toured four of the Australian colonies. Three of their members stayed on to form Webb’s Royal Marionettes, under English-born Charles Webb (c.1842-1887). From 1876 to 1887, this company toured throughout Australia, New Zealand, southern Asia, and as far as England in 1881 and Scandinavia to Russia in 1882-1883. They were sometimes advertised as The Royal Australian and Indian Marionettes.

Amateur puppetry flourished in the 1940s and 1950s, especially among teachers, who mainly used glove puppets and marionettes (string puppets). W.D. Nicol (1907-1978) helped found a puppetry guild in Melbourne in 1942, which was responsible for weekly shows at the Littlest Theatre from 1945 to 1950. Edith C. Murray (1897-1988) helped found a puppetry guild in Sydney and also started the Clovelly Puppet Theatre in 1949, which gave performances on Saturdays, mainly by children, for more than twenty years. She was awarded a BEM (Medal of the British Empire) in 1979 and became a Member of Honour of UNIMA in 1980. Some professional puppeteers gained their early experience with Nicol or Murray. In 1952, a tour by the Hogarth Puppets from England, under Jan Bussell, did much to increase the interest in puppetry.

The Beginnings of an Australian Puppetry

An important milestone in Australian puppetry was the appearance of The Tintookies, a large-scale marionette production with Australian characters, which opened in Sydney in 1956. The person responsible was an experienced marionette player from Melbourne, Peter Scriven (1930-1998). Leading professionals provided the story and design, and the pre-recorded dialogue and music. Scriven’s puppet master was Igor Hychka (1914-2001) who had himself worked with Vittorio Podrecca and his Italian marionettes (see Teatro dei Piccoli) in Argentina.

Scriven invested much of his personal fortune in this show, and others that followed, and was behind the formation of the Marionette Theatre of Australia (1964-1988), based in Sydney, initially formed to tour these big productions throughout Australia and South East Asia. The new company received government funding so when the Australia Council was formed in 1968 puppetry was already a category for subsidy. The large-scale marionette touring tradition was kept alive by the Queensland Marionette Theatre of Phillip Edmiston until the 1990s.

The second company to attract sizeable government funding was the Tasmanian Puppet Theatre (Hobart, 1970-1980) of which L. Peter Wilson (b.1943) was Artistic Director. He and Richard Bradshaw (b.1938), at the Marionette Theatre of Australia from 1976 to 1983, began using other puppet forms, often with puppeteers in view, and also created shows for adults. Both companies had talented puppet-makers, notably Ross Hill (1954-1991) and Beverley Campbell-Jackson (1935-1989). The larger shows, often using some kind of rod puppet and having four to six puppeteers, had theatre seasons and limited touring, while smaller shows with two to four puppeteers were created for school tours.

Recent Activity

This pattern of operation continues with current subsidized companies, such as Polyglot Puppet Theatre in Melbourne, founded in 1978 by Naomi Tippett, Terrapin Puppet Theatre in Hobart, Tasmania, founded in 1981 by Jennifer Davidson, and Spare Parts Puppet Theatre in Fremantle, Western Australia (near Perth), founded in 1981 by L. Peter Wilson. These companies tour mainly within their own states.

Spare Parts and Polyglot have their own theatres, as did the Marionette Theatre of Australia from 1983 to 1988, but it seems almost impossible for an Australian puppet company to maintain a fixed venue without also touring. The Pilgrim Puppet Theatre of Robert and Nancy Akins in Melbourne, attractively housed in a converted church, only lasted from 1977 to 1980.

The tiny Puppet Cottage in Sydney was supported by a local tourist authority and gave free public shows from 1992 to 2004. It was begun by Basil Smith, a Punch-and-Judy man from England and was then managed by the Sydney Puppet Theatre of Sue Wallace and Steve Coupe. Other puppeteers made guest appearances. Also in Sydney, without any subsidy, Jackie and John Lewis opened a small puppet theatre, Puppeteria, for their glove-puppet shows in 2000 and an additional Puppeteria in another suburb in 2003.

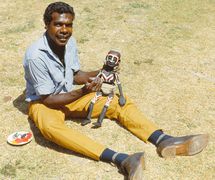

Unsubsidized shows, usually presented by one or two people, tour mainly to schools. An early example from 1934 was the marionette show of Kay and Allan Lewis of Sydney. David and Sally Poulton have toured some of Queensland in their own small aeroplane. Solo puppeteers such as Richard Bradshaw (shadow puppets), Dennis Murphy (glove puppets), Murray Raine (marionette variety) and Richard Hart (ultra violet light/black theatre) have also toured internationally. Neville Tranter, the Netherlands-based solo puppeteer, began in Australia. Norman Hetherington (1922-2010) created and manipulated Australia’s best-known puppet, the marionette Mr Squiggle, who appeared on television from 1959 to 2001. Norman Hetherington was made a Member of Honour of UNIMA in 2008.

The Tasmanian Puppet Theatre’s most important production was Momma’s Little Horror Show (1976), later simply Momma’s, for young adult theatregoers. The show, created and directed by Nigel Triffitt (1949-2012), then new to puppetry, marked a significant shift from traditional puppet forms into “visual theatre”.

Major Trends

The term “visual theatre” encompasses shows where text is secondary or non-existent. Sometimes live actors feature with the puppets or animated objects, while the manipulators may be visible, partly visible, or hidden using “black theatre” effects. Handspan Theatre Company of Melbourne (active from 1977 to 2002) was founded by a group of six young puppeteers wanting to break free from traditional puppet forms and explore visual theatre. It became a collective of about thirty members. Noteworthy shows for adults were Secrets (1983) created by Nigel Triffitt, and Pablo Picasso’s Four Little Girls (1988) directed by Ariette Taylor, both of which toured internationally. Peter J. Wilson, a founding member of Handspan, became in 1993 Artistic Director of Skylark Puppet Theatre of Canberra (active from 1984 to 1998). This company mounted Wake Baby (1996), directed by Nigel Jamieson who comes from a background in physical theatre. It had a season on Broadway in New York. The Dead Puppet Society of Brisbane is a relatively new visual theatre company which has been mentored by South Africa’s Handspring Puppet Company.

The Philippe Genty company from France has made several tours to Australia in the period 1973 to 2004 and has had a strong influence on visual theatre here. The 1996 production, Stowaways, was initially created by the Gentys in Adelaide with five Australian performers.

Since the 1990s, there has been an increased use of puppets with live actors in shows for theatres. This is a feature of the children’s shows created by designer/director Kim Carpenter (b.1950) for his Theatre of Image. The Hobbit, based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s book, originally a 1997 co-production of Christine Anketell with Skylark, appealed to adults as well as children and was a commercial success. The producers of a remounted version of The Hobbit in 1999-2000 were also responsible for The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (2002), based on the book by C.S. Lewis, a piece of musical theatre with live actors and puppets, including a magnificent realistic lion and a supple giant. Philip Millar supervised the construction of the figures for this and The Hobbit.

Large-scale puppets for outdoor shows have been a feature of recent years. Snuff Puppets, based in Melbourne since 1992, have had national and international success with their coarse, bold figures, often dealing with environmental themes. Another company, which is known for its adventurous use of large puppets, including a dinosaur “petting zoo”, is the visual theatre company Erth – Visual and Physical Inc., based in Sydney since 1990. knee high puppeteers (sic), founded in Adelaide in 1995, are particularly known here in Australia and overseas for their giant, metallic stilt figures, “The Android Sisters”, an unscheduled highlight of the last days of the 1996 UNIMA Congress in Budapest.

Notable Australian television puppet personalities include: Mr Squiggle (1959-2001), made and performed by Norman Hetherington; Amanda the Cat (1959-1971), made and performed by Ann Davis; Ossie Ostrich (since 1967), made by Axel Axelrad; and Sebastian the Fox (1963), created for Peter Scriven.

A number of Australian puppeteers have been awarded Churchill Fellowships to study overseas: L. Peter Wilson (1973), Phillip Millar (1993), Sarah Kriegler (2000) and Sue Wallace (2005). Puppeteers who have received the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) are Richard Bradshaw (1986), Norman Hetherington (1990) and Ann Davis (2002).

As Australia has become more multicultural, so has its puppetry, with puppeteers coming from European countries, such as Egypt, Chile, etc. Noriko Nishimoto of Spare Parts Puppet Theatre comes from Japan. Carouselle Theatre Company (active from 1985 to 1997) was founded in Adelaide by six actors from Poland, under the direction of Wojciech Pisarek. The shadow puppetry in The Theft of Sita, directed in 2000 by Nigel Jamieson, was co-directed by Peter J. Wilson and I Made Sidia, a dalang from Bali.

At the same time more Australian puppeteers have been working with groups outside Australia and especially in Asia, and many shows created in Australia have toured overseas. New technologies are also being used and explored. Digital technologies are being used and Terrapin Puppet Theatre has used “virtual puppets”. In Melbourne, Creature Technology, led by Sonny Tilders, devised Walking With Dinosaurs using full-scale figures worked using computers and radio-controls as well as live performers, and the show has played to huge crowds in arenas in North America, Europe and Asia. For their spectacular (and costly) 2013 big theatre musical of King Kong they built a 6-metre marionette with animatronically-controlled features.

Festivals and Institutions

In a country as vast as Australia, opportunities for Australian puppeteers to come together regularly are rare. In Adelaide (South Australia) in 1968, on the initiative of Edith C. Murray, a meeting was held that led to the founding of the Australian Puppetry Guild and UNIMA Australia, in 1970. The Australian Puppetry Guild (1969-1998) replaced the Puppetry Guild of Sydney. In 1980, Maeve Vella, a founding member of Handspan Theatre Company, launched a journal, Manipulation, that more effectively than the guilds united puppeteers as far as New Zealand (the New Zealanders brought out one of the issues). The Australian section of UNIMA was established in 1970; it remains the only organization capable of uniting puppeteers across the island continent. Its irregularly published publication, Australian Puppeteer, replaced Manipulation.

Nevertheless, the opportunities for professional puppeteers to meet continue to be rare. Among the exceptions are the festivals in Melbourne (1975), Hobart (1979), Perth (1988), and “National Puppetry Summits” in Melbourne (2002 and 2012), Hobart (2004), Perth (2008). The small One Van Festival held in Blackheath (west of Sydney) organized by Sue Wallace of the Sydney Puppet Theatre became an important annual event. The 2008 UNIMA Congress and World Puppetry Festival held in Perth, Western Australia, was organized by Spare Parts Puppet Theatre of Fremantle on behalf of UNIMA Australia (see Union Internationale de la Marionnette). The Festival brought together puppet companies and individual performers from all over the country, and was a singular opportunity for Australian puppet theatre to be showcased to the world.

The Lorrie Gardner UNIMA Australia Scholarship Fund bears the name of a former UNIMA Australia president who generously contributed to it through her will. The organization has its own website: www.unima.org.au. O.P.E.N., a valuable electronic newsletter for Australian puppetry, is independently published by Julia Davis and Richard Hart of Dream Puppets and can be accessed on their website: www.dreampuppets.com

In 2004, Peter J. Wilson founded and directed the Post-Graduate Diploma and Masters in Puppetry course at the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne, the only course of its kind in the country. The course was regrettably closed in 2009 in the merger of the College with Melbourne University.

Bibliography

- Bradshaw, Richard. Richard Bradshaw’s Guide to Shadow Puppets. Garden Bay (BC, Canada): Charlemagne Press, 2015.

- Hetherington, Norman. Puppets of Australia. Sydney: Australian Council for the Arts, 1974.

- Parsons, Philip, ed. Companion to Theatre in Australia. Sydney: Currency Press, 1995, pp. 468-470, and individual entries. Nicol, W. D. Puppetry. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Vella, Maeve, and Helen Rickards. Theatre of the Impossible – Puppet Theatre in Australia. Sydney: Craftsman House, 1989.

- Wilson, Peter J., and Geoffrey Milne. The Space Between – The Art of Puppetry and Visual Theatre in Australia. Sydney: Currency Press, 2004.