The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland comprises England, Scotland and Wales, with six counties of the north-east territory of the island of Ireland (known as Northern Ireland), plus several small islands around the coasts of these four main regions. All together these form a nation in the North Atlantic off the north-west coast of continental Europe. The term Great Britain refers only to the island comprising Scotland, Wales and England. The majority language is English; Wales (Cymru in Welsh) is officially bilingual with many Welsh speakers. Scots, a dialect of English, and Scottish Gaelic are also spoken in Scotland and Irish and Ulster Scots in Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy.

Puppetry in the United Kingdom

British puppetry is directly derived from the larger picture of the European puppet stage and is also part and parcel of the British popular drama, of pantomimes and drolls, clowns and jesters.

Since the 16th century there have been multiple references to puppets in various texts, and in 1614 a complete play for puppets was integrated into Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, in which the legend of Hero and Leander was transposed to 17th-century London. This little piece, still entertaining to watch today, incorporates what must be regarded as basic features of popular glove puppetry: great exchanges of bastinado (beatings with a stick) and a totally uncoordinated plot.

The 17th and 18th Centuries

In 1662, Samuel Pepys records in his Diary the arrival of Pulcinella (who he calls Pollicinella) by an Italian puppet player. It seems probable that the puppet was a marionette operated by rod and strings. For the next hundred years this same character, under the name of Punch with a wife called Joan (which much later evolved to Judy), was to dominate the booths (the English travelling puppet stages) as the protagonist of stories from the Bible, and in legendary and historical folk tales, played in the fairgrounds all over the country. (See Punch and Judy.)

In the 18th century in London, a more sophisticated form of puppet theatre saw this same Punch introduced into ballad-operas, burlesques and satires for a more demanding public in little theatres both permanent and temporary. These were directed by such artists as Martin Powell (in Covent Garden), Charlotte Charke (daughter of the talented actor-manager Colley Cibber), Henry Fielding (well-known as the author of Tom Jones, who played under the nom-de-plume of Madame de la Nash), Samuel Foote (mime and dramatist), Charles Dibdin (composer and performer of solo entertainments), and lastly a group of Irish dramatists and artists who played under the name of the Patagonian Theatre.

The 18th century was truly the golden age of puppetry in England (the many venues where they were to be seen have been listed by George Speaight in his History of the English Puppet Theatre). In the second half of the century there were no less than twenty-nine different puppet theatres in London. However, Punch has outlived them all.

The end of the century produced an invasion of Italian marionette performers who presented puppets distinguished by the name fantoccini. Their shows had Harlequin (see Arlecchino) as the central character, rather than Punch, and featured clever trick and transformation puppets. In the mid-19th century the English marionette players began to use only stringed figures controlled from above, because of the demands of the trick puppets. The stiff rod fixed to the head, preserved in many European folk puppet traditions, was largely abandoned.

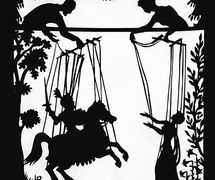

At the same time, the shadow shows occasionally to be seen since the 17th century, reappeared under the French title of “ombres chinoises” (Chinese shadows), imported by French and Italian artists, the shows consisting of a number of short sketches, among which The Broken Bridge was the most popular and enduring.

The 19th Century

The string puppet shows in 19th century England followed a new path, without Punch and with a repertory of popular melodramas and pantomimes, almost always following productions already performed by actors and other players on the stages of the contemporary theatre. Nevertheless Punch could still be found in the form of a glove puppet in the booths of the travelling puppeteers, in satirical and salacious sketches played to a working class audience.

In London, during the first half of the 19th century the theatre was dominated by melodrama, romance and pantomime, all mounted in a powerfully visual manner. The spirit of that theatre was captured by black and white or coloured prints (“Penny Plain, Tuppence Coloured” were the prices) of scenes and characters based on favourite productions then in London. When cut out and placed on a miniature stage, whole productions could be recreated at home. Tiny cardboard figures in elegantly hand-painted costumes strutted their stuff on the small stage with the panache of an Edmund Kean or a host of Regency and Victorian actors in what came to be known as the Toy Theatre (Paper Theatre in other European countries) which embodied the very spirit of romance and excitement.

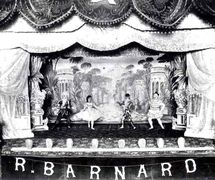

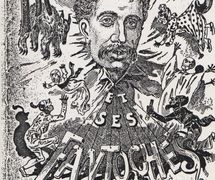

The second half of the 19th century saw a remarkable revival in marionette shows played in the growing number of music halls and also in portable theatres transported around the countryside. Generations of marionette showmen (notably Bullock, D’Arc, Delvaine, Holden, Chester and Lee, Wilding, Barnard, Clowes and Tiller), established companies which toured abroad: all over Europe, the United States and even Australia and the Far East, presenting fashionable melodramas, music hall turns and pantomimes. Before they were submerged by the cinema, these British troupes of worldwide renown, made a supreme contribution to the art of the marionette. (See Bullock’s Royal Marionettes, D’Arc’s Marionettes, Thomas Holden, Tiller Clowes Marionettes.)

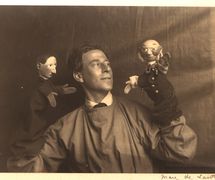

With the dawn of the 20th century, certain modernist and symbolist artists, and disciples of the Arts and Crafts movement, became enthusiasts of puppetry. These were artists who saw it as a medium in which the creator remained in total control of the work. They built figures (usually sculpted in wood), clothed them, presented them in pieces often especially conceived for them, and finally manipulated them. As early as 1897 Arthur Symons wrote that the puppet was capable of presenting “a more intimately poetic sense of things than the merely rational appeal of modern plays”. Ten years later, Edward Gordon Craig in turn wrote: “Who knows whether the puppet shall not once again become the faithful medium for the beautiful thoughts of the artist?”

Towards the Modern Puppet

In the course of the next forty years, a number of artist-craftsmen attempted to realize the aspirations of Craig. Examples are William Simmonds, with his solo shows full of charm and delicacy; Walter Wilkinson who gave new life to the glove puppet through the simple mimes and ballads he presented on village greens all over Britain and beyond.

The foundation in 1925 of The British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild followed in 1927 by the London Marionette Theatre with the support of such luminaries as Gilbert K. Chesterton and Edward Gordon Craig, ushered in a new era for the British puppet scene. In the 1920s and 1930s, the activities of puppeteers such as Waldo Lanchester (with The Lanchester Marionettes), Harry William Whanslaw and Jan Bussell affirmed the power of a performing art capable of attracting a middle class as well as a street and fairground public. For the first time too a small flow of books on the techniques of staging puppetry, notably those by H.W. Whanslaw, began to be published.

For most of the professionals, the period between the two world wars saw the rise of the variety show, in which realistic figures of animals and humans operated by unseen puppeteers performed circus tricks and other sketches. Musical accompaniment was provided by gramophone records; live voices and music were rarely used. The Hogarth Puppets directed by Jan Bussell and Ann Hogarth brought a new impetus in insisting that the production values of the “human” theatre – good writing, acting and scenic design – should be applied to staged puppetry, not simply the values of the craft workshop.

At this time the art of the puppet was enriched by other fine artists encouraged by the European examples of Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee and Oskar Schlemmer (see Bauhaus) among others. The Modernist movement eventually gave birth to the “artist-puppeteer” with a background in fine art, exemplified by Olive Blackham who experimented with a repertory of poetic plays in collaboration with painters, sculptors and scenographers, all exploring the dramatic potential of the puppet. Her productions were borrowed from sources such as the Japanese Noh, medieval mysteries, the plays of Shakespeare, Chekhov and an American amateur, Alfred Kreymborg (1883-1966). This lively desire to enlarge the repertoire was shared by the Hogarth company and by the Lanchester Marionettes for whom George Bernard Shaw wrote a piece: Shakes vs. Shav., and these new directions were encouraged by a wave of imported European talent, refugees from Nazism, including Paul Brann, an influential marionettist, and Lotte Reiniger, whose animated silhouettes for the cinema and theatre are historically important; thanks to her and to the experimental work of Helen Binyon, teacher in the Bath Academy of Art, British shadow puppetry developed so as to earn a place in the artistic repertoire.

Wartime puppetry was otherwise largely limited to anti-Nazi shows in which the national hero, Punch, ridiculed Adolf Hitler and his allies.

After World War II

The 1950s and 1960s brought profound changes, above all in the liberation of the puppet from the imitation of people and animals. A new language gave it freedom both from realism and illusion, at least in the productions where the puppeteers were no longer concealed.

Other post-war changes included the growth of television which in its early years gave rise to the popular belief that puppets were only for young children: the BBC broadcast puppet programmes almost exclusively for the under-fives.

In 1951 the Belgrave Mews Theatre of Edinburgh, directed by Miles Lee, was the only permanent site puppet theatre in Great Britain (it lasted until 1961). Lee’s work attracted the attention of internationally recognized masters such as Sergei Obraztsov. In 1958 the second British theatre specifically constructed for puppets, the Harlequin Puppet Theatre, was opened in Colwyn Bay, Wales, by Eric Bramall and Chris Somerville, and was still active in 2012. There Bramall organized in 1963 and 1968 the first international puppet festivals to be held in Britain. In 1960, John and Lyndie Wright (née Parker) opened The Little Angel Marionette Theatre in London. Their productions emphasized the plastic values of form, colour and lighting applied to literary adaptations of fairy stories and popular legends. (See Little Angel Theatre.)

The discovery of new synthetic materials changed the traditional methods of making puppets, partly displacing the traditionally carved figure; in addition the steady rise of international activity, largely attributable to the work of UNIMA, brought world influences to practices and the exchange of ideas. From the 1950s international festivals revealed the work of the East European groups, which strongly influenced some British practitioners. Because these groups were generously subsidized, a number of British companies also aspired to state subsidy, and to higher artistic standards. The most successful were Jane Phillips’ Caricature Theatre of Wales and the Cannon Hill Puppet theatre in Birmingham, directed by John Blundall, paving the way for a revolution in the perception and financing of puppet theatre. At the beginning of the 1970s the puppeteers were at last allowed to apply for grants to the Arts Council of Great Britain, on the same basis as other theatre companies.

From the 1960s one of the puppeteers who brought about the regeneration of the art form was Barry Smith. His approach was innovative and adventurous, insisting that the puppet had its own discrete theatre language. His shows were for adults, and he was one of the first to present the actor-puppeteer as a character alongside the puppet.

Organizational Support

The prestige of British puppetry grew during the 1970s and 1980s, thanks to a growing number of full-time professionals, access to public funds and a strengthening infrastructure. Three associations promoted the art form: The British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild, the British section of UNIMA, and the Educational Puppet Association (EPA) which under the leadership of the puppeteer, writer and theoretician Alexis Robert Philpott saw in puppetry a medium for improving the quality of life for children and as therapy for the disabled. (See also Violet Philpott.)

In 1974, thanks to the efforts of a small group of enthusiastic non-puppeteers including Penny Francis who successfully raised funds for the enterprise, a national Puppet Centre was founded in London with a large office and a small staff to act as a contact and focal point for both public and puppeteers, launching a dynamic programme of events, workshops, festivals, bursaries, publications and exhibitions. The Centre merged with the EPA in 1975 (see Puppet Centre Trust). Malcolm Knight founded The Scottish Mask and Puppet Centre in Glasgow in 1981 and, also in Scotland, Puppet Animation Scotland was founded in 1984 by Simon Hart and was based in Edinburgh. Among other associations were The Punch and Judy Fellowship and The Punch and Judy College of Professors. There is also a small number of regional associations, the Puppet Place in Bristol now the most active. All have more or less ambitious programmes of activity, mainly workshops and festivals. In 1999, largely thanks to Ray DaSilva, then President of British UNIMA, the various organizations grouped themselves together under the title of Puppeteers UK (PUK). It promotes practitioners, and plays a variety of roles in research, in social networking and the diffusion of information.

The Companies, the Artists, Their Way of Life

Jane Phillips won support from the Welsh Arts Council to found the Caricature Theatre of Wales in 1966 which employed a variety of scenographers, writers, craftsmen and directors brought in for different styles of performance. Based in Cardiff, the company was a pioneering force in British theatre and television puppetry before all of its grant aid was unaccountably withdrawn, forcing its closure after 20 years of life. The Cannon Hill Puppet Theatre, based in Birmingham and directed by John Blundall, followed the example and aesthetics of the great contemporary companies of East Europe and enjoyed a long occupation of the Midland Arts Centre, giving year-round performances from 1968 to 1992. The DaSilva Puppets showed considerable entrepreneurial skills in their tours of halls and theatres up and down the country with large-scale, colourful, musical versions of fairy tales. In 1979 this company founded the Norwich Puppet Theatre in a converted church, which, like the Little Angel, has presented shows by a resident and visiting companies and trained many puppeteers.

In 1991 two researchers, Keith Allen and Phyllida Shaw, were engaged by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation to produce and publish the first enquiry into the state of puppetry in Great Britain. Entitled On the Brink of Belonging, the enquiry notably recommended the need to increase the financing of the art form, the collaboration of the puppeteers with artists of other disciplines, and the recognition of puppetry as an art for adults as much as for children.

In 2005 there were five puppet theatre buildings in Great Britain: the Little Angel, the Norwich Puppet Theatre, the Harlequin Puppet Theatre, the Biggar Puppet Theatre near Edinburgh, and the Puppet Theatre Barge, a floating theatre, home of the Movingstage Marionettes. Puppets could also be seen in many theatres for children, in particular the Polka Children’s Theatre in Wimbledon, London.

Other influential British puppet artists regularly produced work of high quality: Christopher Leith, sculptor and director; Luis Zornoza Boy, fine artist and creator of modernist, original versions of stories for adults and children, who became the director of the Norwich theatre in 1991; Martin Bridle and Su Eaton of Hand to Mouth; Stephen Mottram, sculptor and author of contemplative solo shows; and Oily Cart, innovators in work for mentally and physically disabled children. Faulty Optic, which closed in 2010, was held in high international esteem for their stylized adult work, which united black humour with bizarre themes; Green Ginger, based in Wales, make broadly humorous shows which reveal the influence of the Punch tradition, but using latex hand and rod puppets. Many women exerted a strong influence on the British scene: Lyndie Wright, co-founder of London’s Little Angel Theatre, scenographer and puppet maker; Rene Baker, performer and teacher, in demand internationally; Sue Buckmaster, co-founder of the company Theatre-Rites; Liz Walker (formerly of Faulty Optic) who founded Invisible Thread in 2011; Nenagh Watson and Rachael Field of Doo-Cot. This group, now terminated, was based in Manchester, putting the plastic arts to the service of contemporary social issues. Any list, necessarily incomplete, of the best-known contemporary British practitioners must include Steve Tiplady of Indefinite Articles; Blind Summit, a company founded by Nick Barnes and Mark Down; John Roberts of Puppetcraft, a dynamic presence in the south-west of the country; Mark Pitman and Iklooshar Molara of the popular touring company Garlic Theatre; Nigel Plaskitt, trusted puppetry director/consultant as well as performer for a number of West End stage hits including Doctor Doolittle and Avenue Q; Shona Reppe in the vanguard of 21st century work produced in Scotland, whose Cinderella has joined the pantheon of classic puppet shows. All these artists are also known for their teaching and mentoring. The list needs to be revised every year, as new talent constantly appears. In addition, since the 1980s, the interest shown by practitioners of other theatre disciplines – drama, opera, dance, circus – has endowed puppetry with growing numbers of artists wishing to explore its potential.

The End of the 20th and the Beginning of the 21st Century

At the beginning of the 21st century British puppeteers earned their living from performances and workshops given in arts centres, theatres, schools, community halls, at private gatherings and in festivals at home and abroad. There are several current festivals in Britain, many a once-only event, of which the most notable and, it is to be hoped, enduring are the Scottish Puppet and Animation and manipulate festivals, the Suspense festival in London, the Skipton and Beverley festivals, both in Yorkshire, and the Buxton Puppet Festival in Derbyshire. There are scores if not hundreds of puppet artists working in Great Britain although there has never been a census. Those working in television receive the highest remuneration.

Techniques

The type of puppet currently most often employed is that of the “tabletop” puppet operated from the rear by one to three manipulators. There is also a pronounced trend towards the use of the “hands-on” or directly-worked figure, sometimes with a small rod to the back of the head. The string puppet (string marionette) has not lost its popularity, and both string and rod marionettes are seen frequently. “Object theatre” has been much practised since the 1990s, and the manipulation of “found” objects made from a wide variety of materials in the creation of powerful visual images is in evidence in the work of the newer groups (notably Improbable Theatre, Indefinite Articles and Theatre-Rites). In contrast, the intricately crafted work of the Sharmanka company can be described as part-theatre and part-automata (see Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre).

The tendency towards interdisclipinarity has seen a growing presence of the puppet in the productions of the human theatre. Following the digital revolution, many companies have explored the possibilities of the new electronic media in live performance. Some groups, such as Meg Amsden‘s Nutmeg Puppet Company and the Lempen Company, exploit the potential of the puppet in the preservation of the environment and other social issues. The tradition of the Punch and Judy show continues to be played throughout Britain, and in his function as a national character, Punch sometimes continues his ancient role as a satirical mouthpiece for social and political problems of the day.

Other Contexts

Television and Film

Puppets on television are probably a commoner sight in Britain than in any other country. From the earliest years of the medium there were puppet ventures, chiefly longlasting series only for the under-fives. Ann Hogarth and Annette Mills with the character of Muffin the Mule inaugurated these programmes. Among productions for older children were Gordon Murray’s live broadcasts from his marionette theatre (BBC), Roberta Leigh’s programmes for older children (ITV), and the adventures of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s Thunderbirds (ITV) which continued for years and which still has a cult following.

At the end of the 1970s, Jim Henson (Sesame Street and The Muppet Show) set up a base in England and changed television puppetry for ever, using rod and hand-operated figures performed and filmed with a professionalism not seen before, appealing to adults and older children alike. He was one of those responsible for the heightened status of puppetry in the ranks of the performing arts.

The success of the satirical series Spitting Image (1994-1996), based on the three-dimensional caricatures of politicians and celebrities modelled in latex by Fluck and Law, brought proof that puppets can appeal to sophisticated adults. The concept was adopted by many other countries.

TV advertisements or “commercials” frequently use “real-time” puppet operation as well as frame-by-frame cell or model techniques. In his films made for the cinema Jim Henson pioneered the use of electronically controlled figures, known as “animatronics”, now commonly used, with ever more techniques of puppet animation in constant development.

Among many distinguished names from television and filmed puppetry are those of Harry Corbett, associated with the characters of Sooty and Sweep (real-time glove puppetry), Oliver Postgate, inventor of Captain Pugwash (stop-frame drawn figures), Nick Parks of Oscar-winning Aardman Animation (stop-frame 3-dimensional sculptures), Playboard Puppets of “Button Moon” fame, Nigel Plaskitt, mentioned above, a director of stage, TV and film puppetry, and the puppet-making studios of Darryl Worbey.

Cabaret and Variety

If there is one area of British puppetry which has little need of assistance from any funding body or sponsorship, it is the cabaret and the variety show. The items traditionally presented are a song-and-dance or “personality act”, a transformation or “trick” figure or a circus turn, usually accompanied by recorded sound. Items presented in ultra-violet lighting known as “Black Light” shows are common among the variety acts and may be regularly seen in the work of the Purves Puppets; and in cabaret the English string marionettists, such as Eric Bramall, Roger Stevenson and Ian Thom, were sought after internationally.

Today’s cabaret artists are more likely to perform with live voices and music, and sometimes with a mixture of techniques: some notable contemporary artists are Matthew Robins (shadows), Nathan Evans (animated body parts), Mark Mander (humanettes) and Nina Conti (ventriloquism and hand puppets).

Outdoors

There are more than a dozen processional and community troupes producing street theatre who can claim descent from the American Bread and Puppet Theater of Peter Schumann. The best known are Welfare State International (1979-2005), Horse and Bamboo, and Emergency Exit Arts, all using local participants helping to operate giant figures, shadow puppetry, fire and fireworks for celebratory, dramatic or politically inspired shows.

Training

Education and training for puppetry is provided by individuals, companies and organizations throughout Britain. A Master of Arts (MA) and then a first-degree (BA) course were initiated in 1995 and 1997 respectively by the Central School of Speech and Drama (a college of the University of London), promoting interdisciplinary practice in visual and physical theatre-making. An increasing number of other courses and modules can be found at the London School of Puppetry, the Wimbledon School of Art and Design, Nottingham Trent University, the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and others. The Little Angel Theatre has trained dozens of young puppeteers “on the job”, as has Norwich Puppet Theatre.

The Future

The last thirty years have seen the puppet recognized as a distinct branch of the performing arts, with its own techniques and its own repertoire. The animation of figures and objects has developed in parallel with the abundance of animation seen on television and in the cinema. New companies research new methods and applications, while collaborations with musicians, actors, directors, scenographers, dancers and singers are evidence that the puppet and the animated object are more and more to be seen in theatre productions. The infrastructure too, in terms of theoretical and historical writings, conferences, criticism, museum and archive conservation, support institutions and above all training, is being manifestly strengthened.

(See also Benjamin Pollock, Gerald Morice, Pelham Puppets, Percy Press I, Percy Press II, Puppeteers’ Company (The), Rod Burnett, Small World Theatre, William West.)

Bibliography

- Allen, Keith, and Phyllida Shaw. On the Brink of Belonging. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1992.[S]

- Beaumont, Cyril. Puppets and Puppetry. London: Studio Publications Ltd., 1958.[S]

- Beaumont, Cyril. Puppets and the Puppet Theatre Stage. London: Studio Ltd., 1938.[S]

- Blackham, Olive. Shadow Puppets. London: Rockliff, 1960.[S]

- Boehn, Max von. Dolls and Puppets. London: George Harrap & Co. Ltd., 1932. Translation of Puppen und Puppenspiele. Munich: Bruckmann 1929.

- Bussell, Jan. Puppets’ Progress. London: Faber and Faber, 1953 [S]

- Bussell, Jan. The Puppets and I. London: Faber and Faber, 1950.[S]

- Collier, John Payne. Punch and Judy. London: Prowett, 1828; rpt. 2002.

- Esquiros, Alphonse. Histoire des marionnettes en Angleterre [History of Puppets in England]. Paris: J. Hetzel, 1869. [S]

- Francis, Penny. Puppetry: A Reader in Theatre Practice. Basingstoke (England) and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. [S]

- Haiman, Joseph, and Helen Haiman. Book of Marionettes. New York: Huebsch, 1920.[S]

- Jurkowski, Henryk. A History of European Puppetry. Vol. I: From its Origins to the End of the 19th Century. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1996.[S]

- Jurkowski, Henryk. A History of European Puppetry. Vol. II: The Twentieth Century. Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1996-1998.[S]

- Leach, Robert. The Punch and Judy Show. History, Tradition and Meaning. London: Batsford Academic and Educational, 1942. [S]

- Lee, Miles. Puppet Theatre Production and Manipulation. Vancouver: Charlemagne Press, 1991.[S]

- Maindron, Ernest. Marionnettes et guignols [Puppets and Guignols]. Paris: Éditions Félix Juven, 1900.[S]

- McCormick, John. “Les Middleton à Lyon” [The Middletons in Lyon]. E pur si muove. No. 1. Charleville-Mézières: UNIMA, 2002. (In French, English, Spanish)

- McCormick, John. The Victorian Marionette Theatre. Iowa City (IA): Univ. of Iowa Press, Studies in Theatre History and Culture, 2004.[S]

- McCormick, John, and Bennie Pratasik. Popular Puppet Theatre in Europe 1800-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998.[S]

- Speaight, George. Punch and Judy, A History. London: Studio Vista, 1970.[S]

- Speaight, George. The History of the English Puppet Theatre. London: George Harrap, 1955; Illinois: Robert Hale/South Illinois Univ. Press, 1990.

- Speaight, George. The History of the English Toy Theatre. London: Studio Vista, 1969. [S]

- Speaight, George, ed. The Life and Travels of Richard Barnard, Marionette Proprietor. London: Society for Theatre Research, 1981.[S]

- Von Boehn, Max. Dolls and Puppets. London: George Harrap & Co Ltd., 1932.[S]

- Whanslaw, Harry William. The Bankside Stage Book. Redhill (Surrey): Gardner, Darton & Co., 1950. [S]

- Animations. London: Puppet Centre Trust, 1976-2000.[S]

- Educational Puppetry Association. EPA, 1957-1980.[S]

- Notes & News. British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild.[S]

- The Puppet Master. British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild, 1930.[S]