The character of Punch was first introduced into England by an Italian puppeteer, Pietro Gimonde, from Bologna (c.1662). It was clearly derived from Pulcinella of the commedia dell’arte and was soon anglicized as Punch. As a rod puppet, he appeared in innumerable shows throughout the 18th century (see Great Britain). However, the old English tradition of glove puppets was not entirely suppressed and glove puppets were still in use, often it seems, to attract audiences to marionette shows in fairground booths. Towards the end of the 18th century, Punch as a glove puppet began to appear on the streets of London. The earliest such appearance that has been recorded was in 1785.

The Street Show

It is not entirely clear whether Punch was a development of the marionette shows that already existed, or whether this was a new importation from Italy. Probably both influences were at work. The glove puppet show retained many features of the English marionette play: Punch was accompanied by a shrewish English wife, Joan, whom he regularly beat; and he was carried off by the Devil at the end of the show, though by the end of the 18th century he was beginning to conquer even the Devil. On the other hand, the new glove puppet show introduced a live Dog called Toby, which had been a feature of the Italian glove puppet Pulcinella shows, and – apparently from the same source – Punch was condemned to be hanged, but, as now, persuaded the Hangman to show him how by putting his own head in the noose, upon which Punch promptly hanged him. For some unknown reason, Joan had changed her name to Judy by 1818, and had a Baby, whom Punch threw out of the window.

A new character, Clown, created by the famous Joseph Grimaldi for the English Harlequinade, was added to the cast with the Doctor, a Beadle or Policeman, the dog’s Owner, and as many other characters as the performer found appropriate. The play still consists of a series of interviews between Punch and one of the other characters, each of whom – except for the Clown – is quickly disposed of by Punch’s stick. Any dialogue is subsidiary to the action, but Punch should always speak through a “squeaker” or “swazzle” (called pratique or sifflet-pratique in French and known under various names in other countries), a special ingredient of puppet shows since at least the 17th century (see Voice).

In 1828, a text of the show was published, illustrated by George Cruikshank, and based largely on the performance of an Italian showman called Giovanni (anglicized as George) Piccini (1745-1835) who had come to London in 1779. This tended to establish a basic format for the play which became a popular feature of the English streets. Unlike the show in other European countries, there has never been more than one Punch play for the popular glove puppet show, but this has been capable of endless variations. An essential feature was the “pardner”, or “bottler”, who collected money from the spectators, played the pipes and drum, and sometimes entered into dialogue with Punch.

From Railway to Motor Car

The expansion of the railways in the 1840s led to a growth of new venues for Punch, particularly at the seaside. But versions of the show were also to be found in pantomimes, the music hall, at private parties and at almost any large public gathering. Perhaps the grandest of these was on June 22, 1887, in London’s Hyde Park where the Jubilee of Queen Victoria was celebrated with twenty-five performances.

During this period, the names of several families became associated with the show. The Smith family in particular had branches in many resorts; the Baileys were at Buxton and Harrogate; there were the Jessons, the Maggs, the Greens, and the Codmans played in both Liverpool and Llandudno. Samuel Bridges and others were touring the country in the style of “Codlin and Short” (characters from Charles Dickens’ Old Curiosity Shop), while showmen like Alfred Le Mare and Douglas Alexander combined performing with prop-making and keeping a shop.

In the 20th century, the arrival of the motor car made street performances increasingly difficult. Although a few showmen like George Pegram and Joe Beeby tried to keep the street tradition alive, the show’s main public was at the seaside. In 1939, the journalist Gerald Morice did a survey for the trade newspaper The World’s Fair which identified forty-four Punch men with summer pitches at seaside resorts. By the end of the 20th century, this had declined to no more than twelve.

Nonetheless, the show has never lost its popularity. Following publication of the first script in 1828, a variety of books and ephemera have appeared. The growth of new media has provided further opportunities. Henry Bailey’s show was filmed in 1901 (Mitchell and Kenyon 608), Punch’s first radio performance was May 8, 1923 played by James Portland, and Fred Tickner gave the first performance for television on October 9, 1937.

The Tricentenary

The celebrations marking Punch’s 300 years in England took place on the May 26, 1962 with a church service and public shows in Covent Garden. This event, organized by the Society for Theatre Research and the British Puppet and Model Theatre Guild, was perhaps the largest gathering of Punch showmen since Queen Victoria’s Jubilee and was only exceeded by the 325th anniversary celebrations in 1987 organized by Glyn Edwards and Maggie Pinhorn.

In Great Britain Percy Press I was filmed several times, as was George Prentice in the United States, performing Punch in vaudeville. A full-length film, The Punch and Judy Man, starring Tony Hancock, was released in 1962. Documentaries such as Success Story (BBC, 1975), Punch and Judy (Arts Council, 1982) and As Pleased as Punch (Central TV, 1987) explored the history and appeal of the show. Since the 18th century there have been various stage productions with Punch played by actors, dancers and opera singers. He has also appeared numerous times in literature.

The first attempt at forming a society of Punch men was made by Oscar Oswald in 1955. His “Association of Punch Workers” folded with his death in 1976, but in 1980 Percy Press II founded the Punch and Judy Fellowship, followed in 1985 by the initiation of the Punch and Judy College by “Professors” Glyn Edwards and John Styles. In 2012, both organizations are still active.

In 1975, Covent Garden lost its market and in order to help the regeneration of the area, the organization “Alternative Arts”, headed by Maggie Pinhorn, arranged a neighbourhood festival in collaboration with the Rev. John Arrowsmith (vicar of St Paul’s Church). This was the first “May Fayre” held in 1976 in the grounds of St Paul’s to “celebrate the art of puppetry near the spot where Samuel Pepys first saw Punch in 1662”. The Covent Garden May Fayre has become a major event in the Punch and Judy calendar. Other festivals dedicated to Punch are also organized around the country by the Fellowship and the College.

Punch and Judy up to the Present

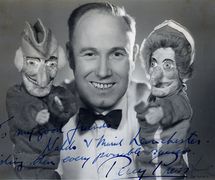

Of the families connected with the show in the Victorian era, the Greens, Jessons, Smiths, Carcass, Codmans and Maggs continued into the 20th century, with the Codmans and the Maggs still active in the early years of the 21st. During the 20th century, many other showmen came to prominence, the most famous being Percy Press I. Others included Bruce Mcleod, Tom Kemp, Bryan Clarke, Samuel Bridges, Frank Bolden, William Jesson, John Stafford, Walter Manley, Claude North, Stanley Quigley and Franklin Spence. Among Punch men who have also constructed figures for others the best known are Fred Tickner, Wal Kent, Quisto (Edwin Simms) and Bryan Clarke with Clarke the most prolific and still active in 2012.

The writings of George Speaight, Gerald Morice, Robert Leach and Michael Byrom have all added significantly to our knowledge of the show, and Sydney de Hempsey, Edwin Hooper and Glyn Edwards have all produced “How to do” books with scripts (Hooper’s “Supreme Magic Company” sold scripts and puppets worldwide). Both Roselia (Thomas Rose) and George Blake have influenced the style and construction of the Punch booth itself. There are many others too, working today, among them John Styles MBE, Glyn Edwards, Rod Burnett and Martin Bridle.

The humble street show, where anything that failed to hold an audience’s attention had to be cut or the showman starved, has led to a strong and enduring formula: a live performance in which the active participation of the audience is encouraged. The advent of “political correctness” has led to some performers amending the show with a reduction in the use of the slapstick and the exclusion of the hanging routine. Others have resisted this, however, regarding such attempts as an erosion of the tradition.

The Punch and Judy show remains a popular feature of open-air fêtes, festivals and children’s parties. Today there are over a hundred professors, men and women, who regularly perform the show. Its future lies, literally, in their hands, as long as they have the wit, skill and tenacity that Punch demands.

(See Great Britain, Percy Press I, Percy Press II, Punch and Judy College of Professors, Punch and Judy Fellowship, Swazzle.)

Bibliography

- Bohrer, Thomas M. Punch and Judy. A Bibliography. New York: Bohrer, 1984.

- Byrom, Michael. Punch and Judy, Its Origin and Evolution. London: Perpetua Press, 1978.

- Byrom, Michael. Punch in the Italian Puppet Theatre. London: Centaur Press, 1983.

- Collier, John Payne. Punch and Judy. London: Prowett, 1828; rpt., 2002.

- Cruikshank, George. Punch’s Real History: accompanied by the Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Punch and Judy. The Explanation of the Puppet-Show, and Account of Its Origin. London: S. Prowett, 1828; Thomas Tegg, 1844.

- De Hempsey, Sydney. How to do Punch and Judy. Chicago: Magic Inc., 1976.

- Duchartre, Pierre-Louis. La Commedia dell’arte et ses enfants [La Commedia dell’arte and Its Children]. Paris: Librairie théâtrale, 1955, pp. 194-210.

- Edwards, Glyn. Successful Punch and Judy. A Handbook on the Skills and Traditions of Performing with the UK’s National Puppet. Bicester: DaSilva Puppet Books, 2000.

- Felix, Geoff. Conversations with Punch. Wembley: Felix, 1994.

- Hooper, Edwin. Hallo Mr Punch. Wembley: Felix, 1993.

- Leach, Robert. “The Swatchel Omi: Punch and Judy and the Oral Tradition”. New Theatre Quarterly. Vol. IX, No. 36, 1980.

- Leach, Robert. The Punch and Judy Show. History, Tradition and Meaning. London: Batsford Academic and Educational, 1942.

- Mayhew, Henry. The London Labour and the London Poor. Vol. III. London: Griffin Bohn and Co., 1851.

- McPharlin, Paul. The Puppet Theatre in America: A History, with a List of Puppeteers 1524-1948. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1949.

- McPharlin, Paul. The Puppet Theatre in America: A History 1524-1948. With a supplement, “Puppets in America Since 1948”, by Marjorie Batchelder McPharlin. Boston: Plays, Inc., 1969.

- Morice, Gerald. “Round the Resorts, 1939-52”. The World’s Fair. Oldham, November 1, 1952.

- Phillips, Jane, ed. The Puppet Master. Vol. VII, No. 1. London, September 1962.

- Recoing, Alain. “Punch et Judy” [Punch and Judy]. Les Marionnettes. Ed. Paul Fournel. Paris: Bordas, 1982; rpt. 1985 and 1995.

- Speaight, George. Punch and Judy. A History. London: Studio Vista, 1970.

- Stead, Philip John. Mr. Punch. London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1950.