Located in Central Europe, the Czech Republic (Czech: Česká republika) is bordered by Germany to the west, Austria to the south, Slovakia to the east, and Poland to the north-east. When Czechoslovakia, formed in 1918, peacefully dissolved in 1993, the two constituent states became the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Today, the Czech Republic includes the historical territories of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia.

Puppetry and elements of puppet theatre probably appeared in the regions of Bohemia in medieval times as elements of religious ceremonies and folk customs. There is iconographic evidence from the Middle Ages documenting the use of finger puppets as part of the entertainment performances of comedians at markets and fairs. In the course of the 17th century, English, Dutch, Italian, and later German theatre groups increasingly travelled to the Czech regions, performing with string puppets to augment the attraction of performances by live actors (see Itinerant Troupes, Travelling Puppeteers). Johann Baptist Hilverding, Girolamo Renzi and Josef Anton Geissler were among the first important puppeteers of this period. Many of these theatre people gradually specialized in puppet theatre. The genres and themes of European theatre were mixed in their repertoire and included biblical plays, English tragedies, Italian improvised comedies, and opera librettos. Another popular genre was German Haupt- und Staatsaktionen, a theatrical genre of Baroque style which was popular in Germany and featured heroic, historical and even comic plays with Hanswurst or characters of the Italian commedia dell’arte. Bohemia initially came under the control of the Austrian Hapsburg monarchy in 1526, and related Germanization especially affected the inhabitants of larger towns. Thus these artists mostly performed in German.

The 19th Century

In the second half of the 18th century, however, resistance to such Germanization grew. Puppeteers of Czech nationality also started performing throughout Bohemia, travelling with their puppets to smaller country towns and communities. Gradually a tradition of puppeteering dynasties arose, and within families such as the Maisners, Kopeckýs, Finks, Dubskýs, and Kočkas, puppetry was passed from generation to generation as a family craft. It was during this period that Matěj Kopecký became the most famous puppeteer and an iconic representative of Czech puppeteers during the first half of the 19th century.

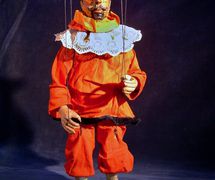

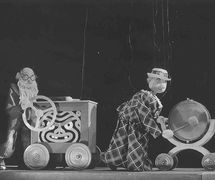

The visual artistry of Czech puppetry was based on Baroque traditions, and puppets routinely displayed the work of folk wood-carvers specializing in Baroque religious sculpture. The puppeteer himself controlled all the puppets and voiced all the characters. Thus a unique staging style came into being in which dexterity, highly stylized vocal displays, and inventive dialogues compensated for the limited movement capabilities of the string puppets. By the beginning of the 19th century, too, the original repertoire borrowed from foreign puppeteers – Faust, Geneviève de Brabant, Don Juan, and Alceste – was enriched with adaptations of Czech dramas. Particularly popular were those tales about knights and robbers and historical-patriotic plays called “Hussites”, such as Jan Žižka u hradu Rábí (Jan Zizka Besieging the Rabi Castle). Several anonymous plays, such as Posvícení v Hudlicích (The Fair in Hudlice), were probably written specifically for Czech puppeteers and are some of the most interesting plays of this period. Pimprle was a typical comic figure of Czech puppeteers and then later Kašpárek, who in his humour reflected that of the popular audiences. During the peak period of the Czech revival, folk puppeteers played a particularly significant role, as they were often the only representatives of Czech theatre to perform for audiences in the Czech countryside. In spite of the prevailing naivety and diminished literary background, these puppeteers could communicate the aspirations of the Enlightenment and Czech revival to their audiences.

In the second half of the 19th century a form of puppet theatre had developed in the cities, mainly in Prague, called jesle (the manger of the Infant Jesus). This Nativity play, initially performed only at Christmas, became a genre of its own.

However, during this period the itinerant puppeteers found themselves unable to keep up with the rapid cultural changes taking place in the country, and stagnation occurred. By orienting their performances toward the less educated populace, they only consummated their isolation from the overall cultural development. Moreover, the introduction of realism complicated matters, as most puppeteers were unable to satisfy its aesthetic premises given the existing means of expression available in the puppet theatre. Even though they were active in Bohemia from the end of the 19th century until the 1950s, the traditional popular puppet theatre became a closed phenomenon. One notable exception was Jan Nepomuk Lašťovka (1824-1877) who attempted to adjust to the new social conditions by renewing his repertoire and staging style.

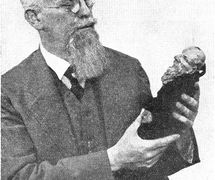

From the middle of the 19th century performing with puppets on small home stages in the so-called “family theatres” became a widespread custom. Many artists, such as Mikoláš Aleš and Artuš Scheiner, together with a number of gifted dilettantes, created these stages to entertain children and friends. Many of these family theatres rose to a remarkable level and became the basis of amateur public performances. As a result, the amateur movement grew in Bohemia at the end of the 19th century. Puppet theatres in schools and various associations including the Sokol (Falcon), a physical training organization that promoted both the physical and cultural development of its members, took up puppetry as a form appropriate for both entertainment and education. Fairy-tale plays dominated the repertoire. Established in 1911, the Český svaz přatel loutkového divadla (Czech Association of Puppet Theatre Friends), sought to seize upon this interest in amateur puppeteering. Its most industrious member, Jindřich Veselý, promoted puppetry through his publications, in particular the magazine Český loutkář (Czech Puppeteer, 1912) which became in 1917 the Loutkář (Puppeteer, 1917-1939). In addition, parents and teachers, visual artists, writers and actors began to take a pronounced interest in puppet theatre, emphasizing its aesthetic values and asserting puppet theatre as a serious art genre.

Czech Puppet Theatre Between the Two Wars

The puppetry movement grew more intense after the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic (1918-1938). Family puppet theatres provided strong foundations, and puppets were being mass-produced while high quality printed decorations were found in many publications. More than two thousand ensembles were active across the Republic and performed regularly for children. Ensembles which emphasized artistic qualities in their work began to exert major importance in the further development of Czech puppetry. Loutkové divadlo Umělecké výchovy (Puppet Theatre of Art Education, 1914-1954) led by the painters Ota Bubeníček and Vít Skála were prominent among that group, as well as Loutkové divadlo Feriálních osad (Puppet Theatre of Vacation Settlements – summer camps for children of poor families) in Plzeň (1914-1936) where Josef Skupa was active since 1917. Major roles were also played by Umělecké loutková scéna Říše loutek (Empire of Puppets, an Artistic Puppet Theatre) established by sculptor Vojtěch Sucharda and painter Anna Suchardová-Brichová in 1920 and still active today, and the puppet theatre Sokol Praha-Libeň (Prague-Libeň Falcon, 1923-1939). While these theatres sought to influence the development of their young audiences, Josef Skupa focused on adult spectators. It was through his cabaret and revue programmes in the Plzeň (Pilsen) theatre that he introduced his original comic characters Spejbl and Hurvínek.

In the 1930s, a new generation of puppet directors began to assert themselves. Jan Malík, Erik Kolár, Vladimír Matoušek and Vladimír Šmejkal changed the production style of Czech puppet theatre, introducing elements from avant-garde theatre. In particular, they emphasized the metaphoric and symbolic possibilities of puppets and strengthened the function of the director. They stifled the previous hegemony of visual artists with a new quality of cooperation between the directors and set designers, and in a number of excellent productions they were able to utilize those elements only specific to puppet theatre. In 1930, Josef Skupa began his professional touring ensemble that achieved extraordinary popularity. Jiří Trnka opened another professional theatre in Prague in 1936, but in spite of its high level of visual artistry, it was not able to survive the economic difficulties of that period.

The war and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia brought new difficulties. During these hard times, however, Czech puppeteers managed to build from their social foundations and continue their creative work. Josef Skupa courageously mounted hundreds of performances with his ensemble, in the process strengthening the spectators’ faith in a just future for the occupied nation. The activities of the PULS – Pražská Umělecká Loutková Scena ensemble (Prague Art Puppet Theatre) – were also noteworthy. The ensemble was established in 1939 by Jan Malík whose stage sequences of Pomněnky (Forget-me-nots) and Sedmikrásy (Daisies) from classic Czech poetry became an important moral support for Czech audiences and prompted similar work in a number of other Czech cities. During the German occupation (1938-1945), some puppeteers including Skupa were allowed to perform. However, many were persecuted. Skupa was eventually imprisoned, and many, especially those of Jewish origin, were sent to the concentration camp in Terezín.

Czech Puppet Theatre After World War II

The majority of the existing professional Czech puppet theatres were founded in 1949 as a result of the implementation of the Theatre Act (1948). This act was the legislative cornerstone for the formation of the extensive theatre network subsidized by the government in Czechoslovakia. By that time, Plzeňské loutkové divadlo Josefa Skupy (Josef Skupa’s Puppet Theatre in Plzeň, created in 1930, then the only professional troupe in the country) had demonstrated how successful professional puppet theatre could be. Furthermore, the tour of the Moscow-based Sergei Obraztsov Central Puppet Theatre (see Gosudarstvenny Akademichesky Tsentralny Teatr Kukol imeni S.V. Obraztsova) in 1948-1949 proved a catalytic event which, among other things, instigated the establishment of professional Czech puppet theatres, in particular the Ustřední loutkové divadlo (Central Puppet Theatre, today Divadlo Minor) in Prague in 1949. The dramaturgy and manipulation techniques of the Moscow group led by Sergei Obraztsov inspired the Czechoslovak puppet community and also influenced official decisions. The Russian example exerted a special influence on Jan Malík and his Central Theatre, particularly in the use of rod puppets, which became from that time on the principal type of puppet used on Czech puppet stages.

After the war Josef Skupa left Plzeň and in 1945 began to establish a new company, the Divadlo Spejbl a Hurvínek or Divadlo S+H (Spejbl and Hurvínek Theatre or Theatre S+H), endowed with its own theatre building. He continued to produce a variety of shows and children’s plays with Hurvínek as the main character. Young artists established within the theatre a creative studio group, Salamandr (Salamander), in an attempt to abolish the monopoly of the string puppet and to invent cabaret items dealing with new topics and more serious human issues. In time Salamandr changed the image of the theatre and widely influenced Czech theatre as a whole. Miloš Kirschner was Skupa’s successor; the latter handed over his figures to him in 1956.

The State provided training for young puppeteers and, in 1952, the Katedra loutkářstvi (Department of Puppetry) was opened in Prague at the Akademie múzickýh umění (Academy of Performing Arts (see Divadelní fakulta Akademie múzických umění or DAMU; in 1990, the academy was renamed Katedra alternativního a loutkového divadla Department of Alternative and Puppet Theatre). The authorities also subsidized the publication and distribution of the magazine Československý Loutkář (Czechoslovak Puppeteer). Many theoreticians and historians of puppetry, such as Jaroslav Bartoš, Jan Malík, Erik Kolár and Miroslav Česal, had their work published in this publication.

The Ustřední loutkové divadlo (Central Puppet Theatre) researched and promoted a new means of expression, portraying an ideological repertoire according to the principles of “social realism”. Thus the theatre popularized a type of rod puppet that was effective in its imitation of human movement. After Stalin’s death, the theatre returned to the folk tradition and looked for broader artistic inspiration. Jan Malík worked with theoretician and director Erik Kolár, who strongly influenced the Central Theatre, combining realism with poetic values as in his famous production Slavík (Nightingale, 1958).

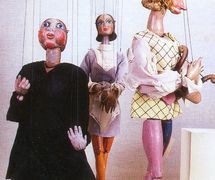

Another important group was Loutkové divadlo Radost (Radost Puppet Theatre), founded in 1945 and nationalized in 1949 in Brno where Josef Kaláb and Jarmila Majerová produced the famous Zlatovláska (Goldilocks, 1953). Some solo players remained: Josef Pehr demonstrated his skill as a glove puppet player with the participation of his resident character Pepiček. Jiří Jaroš introduced a new stage technique, black theatre, when he directed Božena Němcova’s Bajaja (1963) at the Central Theatre using a style both poetic and refreshing. The “black theatre” technique had been used previously and popularized abroad by other artists such as Jiří Srnec, Jiří Středa, the husband and wife team of Lamka and Jiří Procházka. Jiří Jaroš, also famous for his excellent productions including Jevgenij Speransky’s Krása Nevídaná (Incredible Beauty, 1962) and Elena Borisovova’s Tajemství zlatého klíčku (The Secret of the Golden Key, 1964), brought new ideas to Czech theatre. Karel Makonj, founder of the experimental theatre Vedené divadlo (The Guided Theatre) that operated briefly in Prague from 1969 to 1972, deserves special mention for his exploration of the scenic metaphor based on the combination of actors, puppets and mannequins. In his 1969 production of Albert Camus’ La Malentendu (The Misunderstanding), Makonj introduced giant mannequin-like puppets to the stage, and this kind of puppet has subsequently been used by other groups.

From the 1960s to the End of the 20th Century

By the end of the 1960s, Czech artists had almost abandoned socialist realism as they turned to a “theatrical” creative theatre. Apart from the role played by Karel Makonj and his Vedené divadlo with its very significant use of mannequins, puppets and actors, three companies determined the style and artistic trends of Czech puppetry.

Divadlo Loutek (Puppet Theatre) in Liberec was founded by Jiří Filipi but its importance rose under the direction of Oldřich Augusta, who changed the theatre’s name to the Naivni divadlo Liberec (Naïve Theatre of Liberec). Filipi was a writer and made room for the contributions of various directors and designers. Jan Schmid was responsible for the cabaret productions, utilizing different means of expression with a studio group known as Ypsilon. Meanwhile, Pavel Polák and designer Pavel Kalfus were responsible for the children’s productions, giving the impulse for the foundation of a special festival of children’s theatre, Mateřinka, which began in 1973. Markéta Schartova directed most of the shows for older children and adults, such as Carlo Gozzi’s successful Princezna Turandot (Princess Turandot, 1982).

Vladimír Matoušek founded Divadlo DRAK (DRAK Theatre) in Hradec Králové in 1958 with the collaboration of director Jiří Středa and designer and sculptor František Vitek. However, it was in fact director and dramaturge Jan Dvořak who developed the artistic direction of the theatre. Miroslav Vildman instituted a new style in 1964 with Pohádka z kufru (Fairy Tale from a Suitcase) by Jan Vladislav. Still more significant changes came when director Josef Krofta joined the company in 1971. He employed various forms of puppets with actors, objects and other media. The most important production of that time was Jiří Bártek’s Enšpígl (Till Eulenspiegel, 1974), with design and puppets by František Vitek. In the 1980s Krofta took control of the company, producing even more successful shows with Petr Matásek as designer and Jiří Vyšohlid as composer. Examples of Krofta’s work include Píseň Života (Song of Life, after Dragon by Evgeny Shvarts), first produced in 1985, and Kalevala in 1987. He also directed international projects such as Královna Dagmar (Princess Dagmar, 1988), Babylonská věž (The Tower of Babel, 1993) and Mor na ty vaše rody! (A Plague on Both Your Houses!, 2001), inspired by William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a collaboration with international casts.

The third company which was of central importance to Czech puppet theatre is Divadlo dětí Alfa (Alfa Theatre for Children). Founded in Karlovy Vary, Alfa later relocated to Plzeň (Pilsen) in 1963. Its most notable productions are Jan Žižka u hradu Rábí (Jan Žižka Besieges the Rábí Castle, 1974) and Ze starých letopisů (From the Old Chronicles, 1976), directed by Karel Brožek. Since 1967 the theatre has become the home of the biennial festival, Skupova Plzeň (Skupa’s Pilsen Biennale). In 1992, the theatre’s name was changed to Divadlo Alfa (Alfa Theatre) when it moved to its new building.

The collapse of Communism marked in Prague by the “Velvet Revolution” opened new avenues to many artists, especially those from the younger generation. Significant changes followed, such as the adoption of religious themes that had previously been banned. Czech puppeteers achieved a great deal in the area of international cooperation. Especially noteworthy is their role in establishing UNIMA (founded in Prague in 1929) and that of Jan Malík who served as its General Secretary from 1933 to 1935 and again from 1957 to 1972. Czech puppeteers have organized national festivals in Plzeň (Skupova Plzeň) since 1967, in Liberec (Mateřinka) since 1973, and founded in 1952 Loutkárská Chrudim (Puppeteers’ Chrudim), a festival of amateur puppetry. Since 1991, the national showcase of Czech puppet theatre, called Přelet nad loutkářským hnízdem (One Flew Over the Puppeteer’s Nest) has been in existence through the initiative of the Czech Centre of UNIMA. There is also, since 1995, the Spectaculo interesse international puppeteers’ festival in Ostrava. The Chrudim Puppetry Museum, Muzeum loutkářských kultur, Chrudim, was founded in that city in 1972.

In 1994, the newly formed Czech Republic had ten professional puppet companies with their own venues and workshops: Divadlo Spejbla a Hurvínka (also known as Divadlo S+H Theatre S+H) and Divadlo Minor (formerly Central Puppet Theatre) in Prague; Divadlo Lampion (Lampion Theatre) in Kladno; Loutkové divadlo Radost (Radost Puppet Theatre) in Brno; Divadlo Loutek (Theatre of Puppets) in Ostrava; Naivní Divadlo in Liberec; the Malé Divadlo (Little Theatre) in České Budějovice; Divadlo Alfa in Plzeň, Divadlo DRAK in Hradec Králové; and the newly founded Divadlo rozmanitostí (Theatre of Variety) in Most, operating since 1987.

Since 1989, there are also several independent professional associations of note, including Buchty a Loutky (Cakes and Puppets), Divadlo Continuo (Continuo Theatre), Divadlo Líšeň (Líšeň Theatre), Národní divadlo marionet (National Marionette Theatre) of Prague, with its production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and Divadlo Bratří Formanů (Forman Brothers Theatre), noted for its production of the Baroque Opera, which toured Europe and the United States, and for its interesting use of non-traditional spaces. These younger companies, well received by the public and critics in the country and abroad, continue to make use of different types of puppets, but many have recently turned their attention to the classic marionette or have been inspired by their Czech heritage, often searching for less-known puppetry techniques (including shadow theatre). The provocative company Buchty a Loutky combines post-modern elements with elements of film sequences and polyecran (a technique of multiple projection screens) in their productions. Divadlo Continuo has experimented with the style of “nouveau cirque” (contemporary circus developed in the later decades of the 20th century in which a story or theme is conveyed through traditional circus skills). By the end of the century, there was renewed interest in amateur puppet theatre, which witnessed an expansion of young student companies.

Czech Puppetry in the 21st Century

With the early years of the new century, professional Czech puppet theatres have been facing a new challenge: defending their reputation for showcasing modern and inspiring puppet theatre. Interesting dramaturgical changes have been made in the Naivní divadlo Liberec (Naïve Theatre Liberec), Divadlo Alfa (Alfa Theatre) in Plzeň, and Divadlo Minor (Minor Theatre) in Prague, and successful combining of traditional puppetry with the typically irreverent Czech humour have been mounted, among them Tři mušketýři (The Three Musketeers, 2006), directed by Tomáš Dvořák.

Puppet theatre presentations in museum collections have also changed. There are new specialized museums, such as the Muzeum Loutek Plzeň (Puppet Museum in Pilsen) and the Muzeum České Loutky a Cirkusu (Museum of Czech Puppets and Circus) in Prachatice in South Bohemia. Also several puppet theatres have themselves opened smaller permanent exhibitions. These include the efforts of Divadlo DRAK (DRAK Theatre), Loutkové divadlo Radost (Radost Puppet Theatre), and Naivní divadlo Liberec, among others.

Graduates of the Department of Alternative and Puppet Theatre – Katedra alternativního a loutkového divadla – of the Academy of Performing Arts (DAMU) in Prague are coming up with new and very visible projects and engaging in cooperative productions at home and abroad. Meanwhile, both audiences and critics have shown their appreciation for new programmes which combine circus with puppetry, such as the La Putyka show or The Freak Show/Obludárium of the Forman Brothers Theatre.

(See also Alois Tománek, Jan Švankmajer.)

Bibliography

- Bartoš, Jaroslav. Komedie a hry českých lidových loutkářů [Comedies and Plays of Czech Folk Puppeteers]. Praha: Orbis, 1959, 744 pp.

- Bartoš, Jaroslav. Loutkářská kronika. Kapitoly z dějin loutkářství v českých zemích [Puppeteer Chronicle. Chapters from History of Puppetry in the Czech Regions]. Praha: Orbis, 1930; rpt. Praha, 1963, 301 pp.

- Bezdĕk, Zdenĕk. Československá loutková divadla, 1949-1969 [Czechoslovakian Puppet Theatre, 1949-1969]. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 1973.

- Bezděk, Zdeněk. Dějiny české loutkové hry do roku 1945 [History of Czech Puppet Plays Until 1945]. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 1983, 174 pp.

Bezděk, Zdeněk. “Kontinuita a diskontinuita” [Continuity and Discontinuity]. - Československý loutkář [Czechoslovak Puppeteer]. No. 5. Praha, 1969, pp. 81-88.

Blecha, Jaroslav, and Pavel Jirásek. Česká loutka [The Czech Puppet]. Praha: KANT, 2008. - Černý, František, ed. Dějiny českého divadla I-IV [History of Czech Theatre I-IV]. Praha: Československá akademie věd, 1969-1983.

- Česal, Miroslav. Kapitoly z historie českého loutkového divadla a české školy herectví s loutkou. 25 kapitol o českých kočovných marionetářích [Chapters from the History of Czech Puppet Theatre and Czech Schools of Acting with Puppets. 25 chapters about Czech Touring Marionette Puppeteers]. Praha: SPN, 1988.

- Česal, Miroslav. “Kontinuita a diskontinuita II” [Continuity and Discontinuity II]. Loutkář [Puppeteer]. No. 10, pp. 223-225; No. 11, pp. 246-248; No. 12, pp. 270-273. Praha, 1995.

- Česal, Miroslav. “Kontinuita a diskontinuita II” [Continuity and Discontinuity II]. Loutkář [Puppeteer]. No. 1, pp. 4-6; No. 2, pp. 31-33. Praha, 1996.

- Dubská, Alice. Cesty loutkářů Brátů a Pratte Evropou 18. a 19. století [Czech Puppeteers, the Pratte Brothers. Europe 18th and 19th Century]. Praha: AMU, 2011.

- Dubská, Alice. Czech Puppet Theatre Over the Centuries. Praha: International Institute of Puppet Arts in Prague, 1998, 48 pp.

- Dubská, Alice. Dvě století českého loutkářství [Two Centuries of Czech Puppetry]. Praha: AMU, 2004, 302 pp.

- Dubská, Alice. Dvě století českého loutkářství (vývojové proměny českého loutkového divadla od poloviny 18. století do roku 1945) [Two Centuries of Czech Puppetry (Development of Czech Puppet Theatre from the Middle of the 18th Century Until 1945)]. Praha: AMU, 2004.

- Dubská, Alice. V`yvojové promĕny českého loutkového divadla 18. a 19. století [Developmental Changes of Czech Puppet Theatre in the 18th and 19th Centuries]. Loutkář [Puppeteer]. Praha, 1999, p. 20.

- Malík, Jan, and Erik Kolár. The Puppet Theatre in Czechoslovakia. Praha: Orbis, 1970.

- Malíková, Nina. “À la recherche d’une tradition perdu” [In Search of a Lost Tradition]. Czech Theatre. No. 8. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 1994, pp. 78-88.

- Malíková, Nina. Czech Puppets. Praha: Pražská scéna, 1995, 16 pp.

- Malíková, Nina. “L’enfant terrible”. E pur si muove. No. 4. Charleville-Mézières: UNIMA, 2005.

- Malíková, Nina. “Stars Appearing in the Puppeteers’ Sky”. Czech Theatre. No. 12. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 1996, pp. 65-73.

- Malíková, Nina, and Alena Exnarová. Svĕt loutek včera a dnes [The World of Puppets Yesterday and Today]. Chrudim: Muzeum loutkářských kultur Chrudim, 1997.

- Místopis českého amatérského divadla II [Topography of Amateur Czech Theatre II]. Praha: ARTAMA, 2002, 780 pp.

- Středa, Jiří. “České profesionální loutkářství” [Czech Professional Puppetry]. Loutkář [Puppeteer]. No. 3, pp. 110-115; No. 4, pp. 148-151; No. 5, pp. 207-211; No. 6, pp. 254-257. Praha, 2000.

- Vaší Ček, Pavel, and Nina Malíková. Plzeňské loutkářství. Historie a současnost [Pilsen Puppetry. Past and Present]. Plzeň: Divadlo Alfa, 2000.

- Veselý, Henri. Marionnettes et Guignols en Tchecoslovaquie. Praha: L’Institut Masaryk pour l’éducation populaire, 1930.

- Česká divadla – Encyklopedie divadelnich souborů [Czech Theatre – Encyclopedia of Theatre Companies]. Praha: Divadelní ústav, 2000, 615 pp.

- Loutkář [Puppeteer]. Bimonthly magazine founded in Prague in 1917, appeared under different titles and has taken its current name in 1993. Editor-in-chief: Nina Malíková. Theoretical and historical articles, portraits of artists, criticism, scenarios of plays, chronicle of puppet theatre in the Czech Republic and worldwide, festivals.